Wartime Changes for Women and Minorities

A woman saves all her household’s grease and fat to be used for making ammunition |

Women welders in a factor |

Women and Families

With men enlisting or being drafted into the military, women moved into the labor force in large numbers. Before the war, women had limited employment options. African American and Hispanic women typically worked as laundresses or housemaids for low pay. White women had access to better jobs but still few options available to them in the kinds of work they could perform. Standard career options for women included clerical, retail, sales, nursing, and teaching. Many white women worked only until married, and the vast majority of white women were homemakers.

Wartime poster encouraging women to participate in the war effort

Women working for Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. making wartime goods |

A woman working on an airplane motor |

The war created opportunities for women in industrial labor. Collectively referred to as “Rosie the Riveters,” women moved into work roles traditionally available only to men. They worked in shipyards and airplane and tank plants. Women made better money than ever before and performed important work for the war effort. Despite this, the majority of women, white women in particular, remained outside of the paid labor force and all women continued to earn wages below those paid to men. Few women held such highly-skilled and well-paying jobs as riveters. Even those women working in the traditionally all-male industries like shipyards and factores were often relegated to the more menial tasks.

A woman working on a dive bomber |

A woman riveting a plane |

A woman in the cockpit of a bomber

By the end of the war, women received the social message that their work had served a wartime service and that they should be prepared to give up their jobs to returning veterans. Some historical studies indicate that many women wanted to return to the home. These women’s daughters would later use the image of Rosie the Riveter and the memory of women’s contribution to World War II as justification in their demand for greater political and economic opportunities.

Nurse in an Army hospital |

Two grandmothers work to produce wartime items |

Women working on a plane in the Army Air Corps

Did You Know?

The Women’s Army Corps (WACS) marching

Women not only went to work on the home front during World War II but they also participated in the armed services. Different branches of the military wanted women to serve in various support positions because the service freed more men for combat. The Women’s Army Corps (WACs), mostly clerical and administrative workers, numbered 150,000. Nearly 100,000 women joined the Navy. Many women—around 60,000—entered both the Army and Navy Nurse Corps as commissioned officers. The Women’s Air Force Service Pilots (WASPs) included many women who had flying experience before the war. These women transported new planes from place to place within the United States. Eventually they transported plans to England.

African Americans

Marchers demand a “Double V”—double victory: defeat Hitler in Europe and racial prejudice in the United States

While there were increased job opportunities for American blacks, some companies and unions attempted to limit their entry or trap them in entry-level, low-paying positions. Kaiser Shipyards was one company that recruited and encouraged black workers from all over the country to move west to work in their shipyards. The company treated them well, playing a critical role in the westward migration of blacks and the dramatic growth of their population in the region. But North American Aviation refused to hire African Americans, and the white union workers of Boeing Aircraft Company also opposed the hiring of African Americans. There were clear limitations to opportunities.

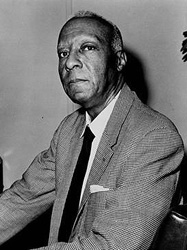

A. Philip Randolph

Under the leadership of A. Philip Randolph, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began a campaign of protest against this wartime discrimination. The group fought for “double victory”—victory against the Axis powers in Europe and against racial prejudice in the United States. Not only were black activists demanding an end to discrimination in defense jobs but they also targeted segregation in the military, with limited success. Randolph and other leaders rejected the traditional tactics of polite protest and petitioning the government for assistance. Rather, they used direct confrontation. Randolph and other activists planned a massive march on Washington, D.C., to demand an end to discrimination. President Roosevelt attempted to defuse the situation by asking Eleanor to intervene, soliciting the aid of other politicians, and finally meeting with Randolph in the White House. All of these efforts did nothing to deter Randolph and the NAACP leadership. In order to prevent the march and possible domestic turmoil, FDR signed Executive Order 8802, which was issued on June 25, 1941. This order effectively banned discrimination on the basis of race, creed, color, or national origin in war-related work contracts. In order to enforce the new mandate, a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) was established with the power to investigate and correct problems. Some companies and unions continued discriminatory practices, and Roosevelt strengthened the FEPC, which investigated and prosecuted instances of discrimination.

The support of the federal government, the increased job opportunities, and African American participation in the war led to more aggressive activism by the NAACP and the newly created Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). They claimed that they were fighting for a “double-V”: victory over fascists overseas and prejudice at home. This was a pivotal moment in the course of American history and for blacks in America, reinserting the federal government into the issue of racial discrimination and also demonstrating that direct, confrontational activism could compel the federal government to support African American rights. Click and drag on the World War II Timeline for 1943 to learn more about the most important events of the war.

Navy yard employees |

African American soldiers in France |

Military mechanic working on a vehicle

Did You Know?

Members of the Tuskegee Airmen

Ever heard of the Tuskegee Airmen? They were a group of African American pilots in the Army Air Corps that escorted bombers to their drop-off locations. The airmen also participated in combat operations. In the Mediterranean theater, for example, they flew 15,000 sorties and destroyed over 260 enemy aircraft. Learn more about them at their website and if you want to see Hollywood’s version of their story, watch the 1995 film The Tuskegee Airmen featuring Laurence Fishburne.

Japanese Internment Camps

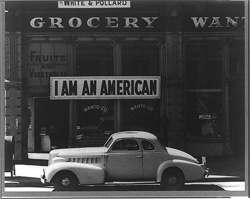

Dorothea Lange photograph of a Japanese American business owner hung this banner outside his business the day after the Pearl Harbor attack. The owner was soon “relocated” to an internment camp.

The internment of the Japanese Issei and Nissei (First and Second Generation Japanese Americans) was one of the great tragedies of World War II. Japanese Americans migrated to the United States to find work in the late 19th century and by WWII, many were second or third generation Americans. The attack on Pearl Harbor caused many Americans to suspect the loyalty of these Japanese Americans, especially as paranoia along the West Coast reached a fevered pitch. Large cities like San Francisco prepared for attacks from the Japanese, and some officials claimed that ships leaving the Columbia River came under submarine attacks. Rumors spread that the Japanese American community along the Pacific coast was rife with spies and saboteurs. An official report by Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts stated that Japanese-American spies in Hawaii assisted the Imperial government with the attack. The fact that no documentation supported this bore no weight as the suspicions against Japanese Americans increased.

Dorothea Lange photograph of a family waiting to go to an internment camp

Fearing the tense situation, many Japanese abandon the coast and move to other parts of the country before a “freeze” locked them into place. On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed and issued an executive order leading to the immediate detention of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Because of the order’s abruptness, Japanese Americans had little time to prepare for evacuation. They could not adequately sell their properties, take care of possessions, or even pack well for a journey with an undetermined ending. Most of the property they left behind would be lost to white American neighbors who took it as soon as the government relocated the Japanese Americans. Despite relocations being blatant violations of American’s civil liberties, few citizens protested the internments or stood up for the rights of Japanese Americans.

The government shipped approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans to “relocation centers.” Most of the ten internment camps were located inland in western states like Arizona and Wyoming. Once placed in a camp, Japanese Americans moved quickly and energetically to improve their situation. They cleaned the buildings they were housed in, built separating walls for families, and created schools, newspapers, markets, and their own municipal services like police and fire departments. Some Japanese Americans received permission to leave internment camps and provide much needed wartime labor picking potatoes, sugar beets, and other crops.

Many Japanese Americans in the camps were determined to prove their loyalty. Some young men volunteered to serve in the military, and a Japanese American corps that served in Europe became the most decorated American unit of World War II. It also should be noted that those young men who resisted pressure to join the military came under severe criticism within their own community; many were ostracized in the post-war years.

Upon their release from the camps in December 1944, Japanese Americans attempted to return to their former lives and communities. Many spent years trying to rebuild their savings and property; in most cases it was impossible to regain the land, homes, and businesses they had lost. The U.S. Congress recognized the injustice of the relocation and internment and the flagrant violation of Japanese Americans’ civil liberties and authorized reparation payments to survivors during the Clinton administration. Learn more about the Japanese American internment camps through the Internment Camp interaction.