WPA graphic

The Second New Deal (1935-1937)

Though public support for Roosevelt remained high as 1934 ended, the Depression had not significantly subsided. First New Deal experiments aimed at relieving major symptoms of the economic downturn had energized the public but had not relieved the suffering. Such stubborn problems as unemployment convinced many in the administration that a new round of programs was needed to target deeper systematic issues within the American economy. The Second New Deal attacked these with the same improvisational non-ideological approach seen in the first two years of the administration. As with the First New Deal only a few, representative laws and programs of the Second New Deal will be discussed.

Works Progress Administration

Harry Hopkins

Unemployment remained at roughly 20 percent throughout 1934 and 1935. Some Roosevelt administration planners argued that early efforts to ameliorate the problem, such as the CCC, FERA and PWA, represented temporary means not adequate to the challenge. By 1935, New Dealers determined that a permanent system of government employment for the unemployed was preferable to any sort of direct payments or dole system. In this scheme, the government would take the role of employer of last resort. When an economic downturn increased unemployment, the government would provide jobs, and when the economy improved, government employment programs would shrink as workers reentered the private economy.

An artist draws an illustration of WPA construction workers.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) received congressional approval in early 1935. It aimed to employ men and women over age twenty-four in a growing range of projects. With a $4 billion budget, it represented the largest peacetime budget item in American history to that point. From its launch in 1935 until it ended in 1943, the WPA employed a total of 8.5 million workers. At its height, 3 million people worked for the massive organization, roughly 20 percent of the American workforce. It built 650,000 miles of highways and roads, 125,000 public buildings, 8,000 parks, and various other projects. WPA jobs paid less than the prevailing wage, so an incentive remained to seek employment in the private economy. The massive scale of the program and its ability to benefit individuals and communities allowed the Roosevelt Administration to please its allies, but also drew criticism. Since WPA projects were administered locally, money flowed through state and municipal political networks and machines but those local connections fed accusations of graft and waste from discontented conservatives.

Federal Theater Project production of MacBeth.

Headed by close Roosevelt advisor Harry Hopkins, the WPA reached beyond normal public works and into the arts, historic preservation, and social research. The WPA’s Federal Writers’ Project funded budding literary talents with work writing local guidebooks, indexing and cataloging historical records, and interviewing people for oral histories. The Federal Music Project’s 225,000 performances reached 150 million Americans and provided 500,000 kids with free music instruction. Controversy dogged the Federal Theater Project, which employed thespians with radical political views and pioneered experimental theater projects—such as an all-black adaptation of Macbeth directed by the young Orson Welles. Theater Project funds helped produce more than 900 plays by the end of the project. Visual artists, such as painters and sculptors, worked within the Federal Arts Project producing public art, advertising for government relief efforts, and exhibiting their work. Click on the images below to learn about New Deal art displayed in post offices throughout the United States.

Web Field Trip

Read some of the slave narratives recorded by members of the Federal Writers’ Project.

Many legacies of the WPA remain today. Much of the building done at Dallas’ Fair Park to house the Texas Centennial Exposition remains home to the Texas State Fair. The buildings, including the elaborately decorated Hall of State, offered venues not just for construction work, but also for artists to use their talents. Modern scholars’ understanding of antebellum slavery is heavily influenced by the Slave Narratives recorded by the Federal Writers Project. Had these interviews not been undertaken by government-paid writers and researchers, slaves’ perspective on the “Peculiar Institution” might have been forever lost.

Eleanor Roosevelt

National Youth Administration

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s influence on her husband’s policy decisions contributed to the controversy. For the most part, she represented FDR’s liberal conscience, calling his attention to problems and people that did not immediately interest him or that might be politically unpopular. She toured the nation for him, bringing back first-hand reports on the progress of New Deal initiatives. She had her own clique of activist friends and her own base of influence, notably through her syndicated newspaper column My Day. Though the Roosevelts’ marriage had become something more like a political partnership, FDR respected her advice and sometimes acted on her recommendations. Find out more about Eleanor’s opinions and contributions by learning about her “My Day” newspaper column in the in the My Day Blog interactive.

Eleanor Roosevelt became acutely conscious of a potential problem looming in the future because of the effects of the Depression on American youth. Many young Americans lacked skills and work experience because of the economic downturn and the resulting weak job market while other young people had to delay or even forego continuing their educations into high school and beyond. In the 1930s, only a fifth of Americans graduated high school and barely a tenth attended college. This small minority of Americans represented the future doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers, and other professionals of the future. Dropout rates from both secondary and higher education skyrocketed during the economic downturn, presenting the possibility of a shortage of such professionals in the decades ahead. Since parents’ educational levels correlated closely with the educational attainments of their offspring, the implications for the nation’s future prosperity alarmed the first lady.

Did you know?

Lyndon Johnson shaking FDR’s hand.

NYA operations differed on a state-to-state basis, with state and local administrators using federal dollars where and how needed. In Texas, twenty-six year-old Lyndon Johnson presided over the NYA, launching projects that kept students in school during the academic year and gave them summer jobs during the summer. The organization began the Texas state highway roadside parks program, building simple picnic and rest sites throughout the state. Like most New Deal programs, NYA had its share of discrimination in hiring and in benefits. Despite opposition and criticism, Johnson worked to provide equal pay and opportunity to black and Hispanic youth with the Texas NYA.

The National Youth Administration (NYA) resulted from those concerns and her ability to influence the president. The NYA provided on-campus jobs for college students, making payments directly to the educational institutions that hired them. Jobs included clerical work and maintaining campus grounds. High school students also had access to government funded work to keep them in school. During the summers, students received jobs so that they could save cash for the coming year’s expenses. NYA provided work to both men and women, though jobs were often assigned on a gendered basis—for example, a common assignment for NYA women involved tending children in WPA sponsored nurseries. By the time the United States entered World War II, the NYA had assisted 600,000 with higher education, supported 1.5 million high school students, and helped another two million young people ages 18 to 24. The agency provided opportunities for youth to gain skills and experience and, just as importantly, kept them out of the wider job market, leaving those employment opportunities to older workers.

Wagner Act

Robert Wagner

Despite the intentions of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), organization of American labor proceeded at a slow pace. While Section 7a had required participants in the NRA codes to adopt maximum hours, minimum wages, and allow union organization, from its inception many businesses co-opted unionization or undermined the effect of the law. Companies established their own “independent” unions that had little autonomy from management. Others employed blacklists and other techniques to inhibit unionization and isolate potential activist workers. Some rejected any bargaining with unions whatever. By early 1935, the NRA tottered on the brink of collapse, awaiting the court decision that eventually killed it. Business took advantage of the lack of oversight.

In 1934, New York Senator Robert Wagner first proposed a bill to remedy these flaws. FDR withheld his support for the measure throughout 1934 until it became clear that momentum favoring it assured its passage. When it became clear that the bill would pass in 1935, Roosevelt threw his support behind it. By that time the president was looking ahead to the 1936 presidential election. Support for the Wagner Act represented part of his plan to turn the 1936 election into a campaign against the power of the wealthy corporations.

The Wagner Act created a much more favorable environment for unionization. By the end of the 1930s, a third of all American workers belonged to a union, and the power of major organizations such as the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations had become a force to be reckoned with. Wagner Act provisions banned company unions, mandated that employers negotiate in good faith, and required that employers recognize any union chosen by a majority of employees. The law also created the National Labor Relations Board, granting power to supervise conduct of employers and employees in unionization elections, but also granting it authority to rule as a court in labor disputes.

Social Security Administration

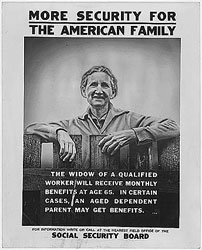

iSocial Security Poster

Did you know?

Frances Perkins

Frances Perkins, who served as Secretary of Labor through Roosevelt’s terms as president, was the first woman to serve as a member of the United States Cabinet.

In the 1930s, elderly Americans fallen on hard times or unable to work had three choices—going on state or local dole, going it alone, or depending on families for support. The Depression hit many families hard, with unemployment or underemployment jeopardizing incomes. Families taking in additional mouths in the form of elderly relatives found themselves in worse shape. Politically, the appeal of Share Our Wealth and the Townsend pension plan highlighted the mass appeal of some effort to help the aged, and by extension, their families.

A special study committee headed by Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins began looking into an old-age pension plan in mid-1934. The plan, proposed and enacted by Congress in 1935, established a system of unemployment, disability, and old age insurance funded by a combination of payroll taxes and mandatory employer/employee contributions. Though Roosevelt had hoped to include all workers from “cradle to grave,” such a plan was fiscally and politically unworkable. Vast elements of the working population, such as those in agricultural, domestic, educational, religious and other charitable work, remained outside the Social Security umbrella. Opposition from conservatives, particularly southern Democrats, helped assure these exemptions. Fiscally, there remained another important problem: the earliest beneficiaries who could expect to draw their first checks in the early 1940s would have paid in far less than they were likely to collect in benefits.

Conservative critics attacked social security as a plan that encouraged the unemployed to shirk work and not save for retirement. Liberal attacks against Social Security centered on its failure to cover all workers and its regressive tax and contribution systems. But, the American middle-class, most of whom benefited from the system, came to be its strongest supporters. Within a decade of its passage, Social Security became viewed as an unassailable entitlement.

Did you know?

Modern day concerns about the solvency of Social Security have not eclipsed the entitlement’s popularity with the general public. In its original form, Social Security was envisioned as a retirement supplement, and was not meant to be a living income. Over the decades, Congress has expanded benefits and increased the number of citizens paying into the system. When inflation pressed fixed incomes in the 1970s, Congress began indexing Social Security payments to meet the so-called Cost of Living Adjustments (COLAs).