The Treaty of Versailles

Although Germany and the Allies signed an armistice in November 1918, the war was far from over. The terms and conditions of peace still needed to be determined. Woodrow Wilson had put forth a lofty set of goals with his “Fourteen Points” speech, but it remained to be seen if his idealistic and wide-ranging plan would actually be put into place.

The Big Four

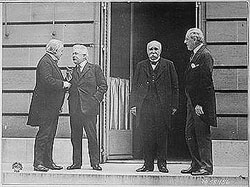

In January 1919, the Paris Peace Conference convened in order to create a peace treaty. Wilson attended himself, and was known as one of the “Big Four,” along with Britain’s Prime Minister David Lloyd George, France’s Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, and Italy’s Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando. One of Wilson’s main objectives was to try to keep the European Allies from “getting even” with Germany. Lloyd George and Clemenceau both wanted to blame Germany for the war, and they wanted to create a peace that ensured Germany’s inability to ever wage war again. Wilson also needed to convince the United States to go along with his plans. Neither of these tasks proved to be easy.

David Lloyd George |

Georges Clemenceau |

Vittorio Orlando |

The Big Four: Lloyd George, Orlando, Clemenceau, Wilson |

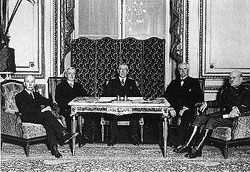

Meeting at the Paris Peace Conference |

The Palace of Versailles |

Redrawing the Map of Europe

The conference struggled to produce a plan for peace. Conference members redrew the map of central and Eastern Europe, destroying the Russian, German, Austria-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires. These western leaders created new nation-states in their place. Many newly independent countries, including Finland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Poland, emerged from the Treaty of Versailles. This means that some people were given self-determination by the treaty. This right was not extended to all nations, disappointing many, including some middle easterners and Vietnamese.

The Battle over Germany’s Fate

Wilson battled with the other powers, particularly Britain and France, over how to handle Germany’s fate. Wilson wanted lenient terms, believing that such terms created the best possibility for a lasting peace. The British, and especially the French—who had suffered tremendously at the hands of the Germans during the war—maintained that Germany had to be punished for its actions. The French believed that their future national security depended on weakening Germany. Ultimately Germany was forced to accept responsibility for causing the war, which was an obvious oversimplification of the war’s origins. Additionally, Germany lost a substantial amount of territory and had to pay $33 billion in reparations. The decisions made on how to treat Germany ultimately led to German bitterness and wrecked the German economy. Rather than “ending all wars,” the treaty had sown the seeds for future conflict. Decades later, American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger referred to the treaty as a "brittle compromise agreement between American utopianism and European paranoia—too conditional to fulfill the dreams of the former, too tentative to alleviate the fears of the latter."

Wilson returning from the Paris Peace Conference

The League of Nations

Wilson’s Fourteen Points certainly influenced the Treaty of Versailles, but the treaty did not incorporate all of Wilson’s provisions—it left out some of the more idealistic and far-reaching suggestions. The Conference did include the creation of a League of Nations in the treaty. Wilson supported the treaty, in spite of its failure to grant “peace without victory,” because he believed strongly in the idea of a League of Nations. He believed that the presence of such an institution would make up for any deficient areas of the treaty and would foster arbitration of any international disagreements.

Senate Rejection of the Treaty of Versailles

William Borah

Wilson managed to convince Great Britain, France, and the rest of the Conference to support a League of Nations. But he had neglected to think about how he would convince his own nation. Wilson had not bothered to include any Republicans in the peace process; the Republicans won congressional elections shortly before Wilson’s return, giving them control of the Senate and of treaty ratification. Republicans objected in particular to the League of Nations' provision calling for member nations to come to the defense of another member in the event of an attack. Ratification of treaties requires the approval of two-thirds of the Senate. When Wilson submitted the treaty to the Senate in July, three groups emerged. Twelve senators—mostly Republicans—opposed the treaty completely and wanted nothing to do with it. They wanted to maintain American isolationism. Led by Senator William Borah, they were called “irreconcilables.” A large group of senators—mostly Democrats—stood ready to support Wilson and sign the treaty as it was presented to them. Forty-one Republicans remained undecided and said they had reservations about the treaty. These “reservationists” followed the lead of Henry Cabot Lodge, the senator from Massachusetts who chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. They said that they would sign the treaty if Wilson would accept and incorporate their reservations. The treaty went to Lodge’s committee, where he drug his feet, refusing to move on the treaty. Wilson decided to take the issue to the people and try to build public support. He embarked on a cross-country speaking tour in the late summer.

Henry Cabot Lodge

Perhaps Wilson pushed himself too hard. In October, he suffered a massive stroke from which he never completely recovered. Although he continued as president, he was physically unable to pursue his goals for the treaty. Cabot Lodge and the Foreign Relations Committee sent two versions of the treaty to the rest of the Senate. One was the original treaty, just as Wilson wanted it. The other version included fourteen reservations that would need to be approved by both the U.S. Congress and by European leaders as well. The Senate voted on both versions in November of 1919. On the original treaty, the vote failed because reservationists and irreconcilables voted against it. The treaty with reservations failed due to the nays from the irreconcilables and the Democrats. Wilson’s “Great Crusade” of World War I came to a disappointing end, with the United States declining to sign the Treaty of Versailles or join the League of Nations.

Although the majority of Americans supported Wilson and World War I and the nation experienced a burst of patriotic sentiment, the end of the war and the failure of the United States to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and join the League of Nations left the American people disillusioned with war. Wilson had set lofty, idealistic goals for the nation, and when the war fell short of these objectives it was a disappointment. The disillusionment and bitterness toward the war lingered and would influence American decision-making early in World War II.