Web Field Trip

America’s best known World War I song, Over There, was written by George M. Cohan. The song was a hit following the United States’s entry into the war. Listen to a 1917 recording of the song by Billy Murray.

The Home Front

As soon as the United States declared war on Germany, the nation began to mobilize for war. The immense size of the war effort and the grave severity of the situation led to a temporary transformation of much of the nation’s economy from capitalism to socialism. The government also assumed greater powers and greater involvement in people’s lives.

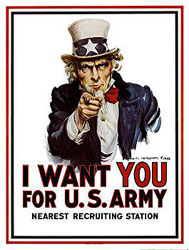

The “I want you” army recruiting poster became the most recognized image of “Uncle Sam” in the United States. James Montgomery Flagg painted the poster in 1916-1917.

Selective Service Act, 1917

The Selective Service Act required 24 million men to register for the draft. The army grew from around 120,000 to 5 million.

Overman Act, 1918

The Overman Act gave the president unprecedented powers and concentrated control in his hands. The act gave him the power to reorganize the government and create new agencies as necessary for the war effort. This act paved the way for many of the following acts and agencies.

U.S. Railroad Administration

William McAdoo

The U.S. Railroad Administration consolidated the nation’s railroads into one gigantic railroad. The industrial railroad leaders could advise and participate, but ultimately decisions were made by the head of the Railroad Administration, William McAdoo. The railroads willingly turned over power, both because they knew it was necessary for the war effort and because the government guaranteed them a profit based on their average profits from the three previous years. The government also promised to maintain the tracks and equipment.

World War I propaganda poster

U.S. Food Administration

Before and during the war, the United States experienced high demand for agricultural products, but had only a limited supply to offer. Led by Herbert Hoover, the U.S. Food Administration told farmers what to produce and to whom they could sell. It also set prices for various goods, preventing inflation. The Food Administration appealed to Americans’ patriotism, instituting a system of voluntary rationing. “Wheatless Mondays,” “Meatless Tuesdays,” and other daily specifications asked Americans to do their part to help conserve food. Hoover declared that “Food will win the war.”

War Industries Board

Bernard Baruch

As with agriculture, American industry felt the pressure of unlimited demand on a limited supply of products. The United States was rich in raw materials, but somebody needed to organize a way to quickly convert the raw materials into usable products. Wilson created the War Industries Board to help industry set priorities and conserve materials. The Board fixed prices for certain commodities and directed the changing of peacetime goods manufacturing to wartime goods. Headed by Bernard Baruch, this was the most powerful of Wilson’s wartime agencies.

Did you know?

Liberty Bond poster

The United States spent about $33.5 billion on World War I. Over two-thirds of this came from borrowed funds, raised largely through patriotic Liberty and Victory Loan drives. The government also collected a great deal of money through taxes. Tax rates increased to more than 75 percent for the highest income bracket. All of this spending actually helped the nation’s economy because much of the money was spent domestically.

Loss of Civil Liberties

Committee on Public Information

Wilson created the Committee on Public Information (CPI) in April of 1917 in order to bolster public opinion for the war and inspire patriotism. Journalist George Creel headed the agency. CPI speakers and writers spread messages across the nation, declaring that the United States needed to fight to protect liberty and democracy. CPI propaganda also illustrated Germany as an evil enemy. The CPI produced many posters during the war, including the iconic “I Want You” Uncle Sam recruiting poster.

Liberty Cabbage and Liberty Sandwiches

Web Field Trip

Hear Lola Gamble talk about how “Nobody would eat kraut” in rural Idaho during World War I in this oral history interview conducted in 1976. Ms. Gamble was a teenager during WWI.

As seen during many of America’s wars and conflicts, concerns regarding security sometimes clash with traditional civil liberties. During World War I, the push for American patriotism coupled with anti-Germany viewpoints and led to the suppression of civil liberties. People who opposed the war sometimes endured verbal abuse or even assault. Some schools outlawed the teaching of German; some streets or towns with German-sounding names were renamed; and Americans began to refer to sauerkraut as liberty cabbage and hamburgers as liberty sandwiches. Conversations in foreign languages were suspected of being spy discussions.

Congressional Legislation

Congress also assisted in the suppression of dissent, passing several pieces of legislation that impeded traditional civil liberties. In 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, making it illegal to make false statements intended to impede the military’s efforts in the war. This interfered with the rights to freedom of speech. Congress also created an Executive Board of Censorship in 1917. This gave the postmaster general the right to open, read, and inspect the mail of private citizens. In 1918, Congress passed the Sedition Act. This made it illegal to speak, write, or publish any disloyal, profane or abusive language about the United States flag, government, Constitution, or military. The government placed Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs prison under this law for making an antiwar speech. Despite being locked up, Debs ran for president from prison in 1920, garnering more than 6 million votes. President Warren G. Harding commuted Debs’ sentence in 1921 and released him.

Did You Know?

See the original flyer Schenck distributed.

Schenck v. United States

In Schenck v. United States (1919), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act. Socialist Charles Schenck distributed thousands of antiwar flyers through the mail. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the Court’s opinion, finding that freedom of speech did not extend to speech that presents a “clear and present danger” of threatening national security or inciting illegal actions. Schenck’s activities would likely have been allowed in peacetime, but the Court concluded that during war they constituted too large a threat to be protected as free speech.

Did you know?

Wheeler in her Spanish-American War nurse uniform.

Wheeler in her World War I American Red Cross uniform.

Few women served overseas as nurses before World War I but one American woman, Annie Early Wheeler, served as a nurse for the Red Cross in three overseas wars: The Spanish American War, the Philippine-American War, and World War I. The images are of Annie Wheeler in 1898 and 1919.

Labor on the Home Front

As the soldiers prepared for war and then fought overseas, Americans on the home front contributed to the war effort in many different ways. In addition to patriotic sentiments, financial support, and food conservation, many Americans went to work outside the home for the first time.

Women

World War II is famous for its mobilization of women into the workforce, but many women went to work during World War I as well. The deployment of millions of American men produced a labor shortage that placed female workers in high demand. Pamphlets and leaflets recruited women to fill much-needed positions.

Women worked in voluntary positions for the Red Cross, as well as in war-bond sales, food conservation, and medical support positions. They also served as police officers, mail carriers, and agricultural laborers. Industry utilized women in railroad crews, loading docks, machining facilities, and saw mills. Approximately one million women took jobs for men who were fighting in the war.

Although many women enjoyed the chance to work outside the home, the phenomenon did not last. Following the war, almost all women—with or without a husband and family—gave up their jobs as the soldiers returned home.

Did you know?

Wartime attitudes and concerns proved helpful to prohibition advocates. In addition to traditional arguments against the sale and consumption of liquor, prohibitionists now had arguments based on patriotism and the war effort. German-Americans owned many breweries, making many Americans unwilling to buy beer. Additionally, the U.S. Food Administration wanted grain to be used for food rather than alcoholic beverages. Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment in 1917, prohibiting the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors. Enough states ratified the amendment by January 1919, and prohibition went into effect on January 29, 1920.

Great Migration

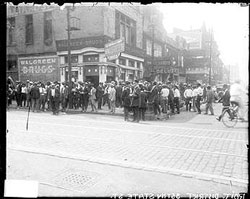

African-American men standing outside a Walgreen’s Drugstore during the 1919 Chicago Race Riot. Like many northern and Midwestern cities, Chicago experienced a tense racial atmosphere with the influx of new African-American residents during the Great Migration.

Southern blacks joined women in seizing the opportunity to fill open job positions when soldiers left for war. After the Civil War and the emancipation of all former slaves, some blacks left the South and made their way to northern cities. The number was small, especially compared to the massive waves of immigrants and rural residents pouring in. As the nineteenth century drew to a close, the migration of blacks northward increased slightly. After 1914, when war broke out in Europe and a war boom hit the American economy, a huge number of blacks—a “Great Migration”—began leaving the South and heading north. African-Americans took labor positions in steel, automotive, and packing facilities. Though some blacks obtained skilled positions in factories, many worked long hours in dangerous conditions.

White racist responses provided a physical and psychological challenge for blacks. Whites incited riots against the unwelcome newcomers in East St. Louis, New York, Detroit, Cleveland and twenty-four other cities. Caucasian residents looted and burned African-Americans’ homes and the police did nothing to stop them. Conditions for African Americans remained imperfect, but they were arguably better than they had been in the South. Letters written to black relatives “back home” show a hope, independence, and self-respect that blacks had not felt below the Mason-Dixon line, causing one man to say that he should have headed north 20 years earlier.

Organized Labor

Organized labor gained strength during World War I because of obvious shortages in the labor supply. The creation of the National War Labor Board also strengthened labor. The board consisted of representatives from government and business, as well as leaders from labor. The NWLB promoted equal pay for women and won an eight-hour day for laborers as well as increased pay for overtime work.

The NWLB granted workers the right to form unions and agreed to mediate wage disputes between labor and management. Workers reciprocated by promising not to slow production through sabotage or walkouts.

Union membership increased 70 percent between 1914 and 1920, thanks to new members from packing institutions, mining, shipbuilding, and railway servicing. Unskilled workers, along with skilled artisans, gained greater respect in unions.