Imperialism in Latin America

The Roosevelt Corollary

Throughout his tenure as president Theodore Roosevelt actively sought to raise the United States to a first rate world power. The president pursued a policy that tried to lessen the influence of European nations within the Western Hemisphere. Traditionally, European countries loaned money to Central and South American nations, and they frequently defaulted on their loans. This resulted in the Western power sending in its military force to seize the respective customs house of the defaulting nation to take taxes in order to pay off the obligation. Roosevelt took steps to curtail European financial lending in order to enhance American power in the region.

The president issued the Roosevelt Corollary as an addendum to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904. The Corollary explicitly warned European powers to stay out of the Western Hemisphere. Roosevelt’s statement asserted that the American government would take over the responsibility of “policing” the region. Specifically, the United States would step in and assume the role of collector if one of the Latin American countries defaulted on its loans. Roosevelt’s policy mitigated the influence and reach of European power. The Roosevelt Corollary established American hegemony within the Western Hemisphere.

The Panama Canal

Roosevelt also sought to control the building of a trans-isthmus canal across Central America. The reasoning behind Roosevelt’s desire to direct the construction of a canal included:

- The goal of increasing the speed of shipping of commerce across the Americas as businesses sought to import and export goods more efficiently.

- The goal of increasing security. Many American officials believed that a canal would speed the navy from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. American military planners cited the example of the voyage of the Oregon for the necessity of a trans-isthmus canal. During the Spanish-American War, the Oregon took two months to travel from California around South America to Cuba to participate in the action against Admiral Cervera.

- The goal of increasing financial profit because the United States would charge tolls to foreign customers in order to gain access to the canal.

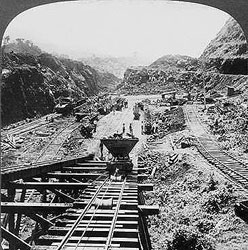

The Canal under construction in 1907

In 1901, the United States repealed the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. The treaty, negotiated in 1850, anticipated the construction of a trans-isthmus canal under joint British-American control. John Hay and Lord Pauncefote, the British ambassador, negotiated a new agreement that granted America exclusive control over a potential canal. Two distinct routes for a canal were considered across the Central American isthmus. The first lay across Nicaragua while the other was in the Colombian province of Panama. An American commission concluded that Panama represented the best site for construction.

In 1903, Secretary of State Hay reached an agreement with the government of Colombia that granted America a ninety-nine year lease across a six-mile area of Panama. The Columbian senate rejected the treaty on the basis that it failed to adequately protect the country’s sovereignty. Columbian senators also thought that the $10 million specified for payment under the treaty was woefully low. This action enraged President Roosevelt, who denounced the Columbian government as a bunch of “highwaymen” attempting to extort money from the United States. Consequently, Roosevelt considered alternative ways to secure an American canal across the isthmus.

Construction of the Canal in 1913

A separatist revolution in Panama presented Roosevelt with an opportunity to secure the isthmus and Roosevelt soon sent military aid to the Panamanian rebels. Roosevelt ordered the United States cruiser Nashville to Panama along with eight other ships. Columbian forces, faced with the threat of American intervention, backed down. As a result, Panamanians gained their freedom and established an independent nation. Roosevelt promptly recognized the Republic of Panama and concluded a treaty with the new government. This treaty, largely a replica of the one the Colombian senate rejected, granted the United States a ten mile wide zone. The agreement also recognized the proposed Canal Zone as sovereign American territory. Roosevelt did not start the revolution, but he has been criticized for his policies in Panama. Learn more about the benefits that the canal brought to the United States in the Are we There Yet interactive on the Panama Canal.

The president, along with many others of his era, treated Latin Americans as inferior peoples. The Corollary, while openly invoking the principle of “police power,” implied that Latin Americans were savages, incapable of governing themselves. The Roosevelt Corollary also justified continued American military intervention throughout Latin America during the 1910s and the 1920s. Some historians argue that the Panama Canal treaty demonstrated Roosevelt’s contempt for people of the region. To many Latin Americans, the Panama Canal represented nothing more than a naked American imperial land grab. Resentment festered among the people of this region until President Franklin Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy reversed this trend in the 1930s.

William Howard Taft and Dollar Diplomacy

William Howard Taft

Theodore Roosevelt’s immediate successors sought to extend American domination over Central America and other parts of the world. President William Howard Taft, elected in 1908 as Roosevelt’s handpicked candidate, pursued a Latin American policy based on economics. The Taft Administration’s endorsement of “dollar diplomacy” reflected America’s rejection of formal empire. Many American policymakers believed that they could control outer lying regions of the globe through economic means. American economic domination meant that the United States could indirectly control the internal affairs of other sovereign nations without resorting to colonial administration or military action. Dollar diplomacy pleased many of the anti-imperialists while providing new investment opportunities and markets for American businesses.

Did You Know?

Theodore Roosevelt’s sometimes heavy-handed views on persuasion could be summarized in an African proverb he quoted: “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” How does this compare with Taft’s use of economic persuasion in Dollar Diplomacy?

In 1911, the United States government allowed American banking companies to service loans that Nicaragua had obtained. Nicaragua defaulted on the loans, and the United States government took control of that country’s customs house. The Taft Administration thought that American economic stability would preserve internal order in Nicaragua but it did not. By 1912 the United States sent in a force of Marines to put down a potential revolution. These events illustrated the ineffectiveness of dollar diplomacy. Despite American pronouncements that disclaimed any interest in territorial expansion into the region, many Nicaraguans still feared their neighbors to the north.