Native Americans and the West

The thousands of migrants to the West showed little regard for the peoples already living in the region. Settlers believed the Indians were socially and genetically inferior and felt justified suppressing, subduing, and removing them from the plains and prairies. Indians struggled to preserve their communities and food sources in the face of mass migration and disruption. By 1900, the rich native cultures were all but gone, and settlers had established dominance in the West.

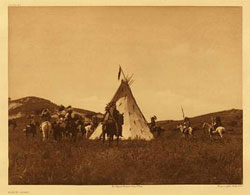

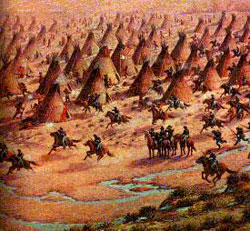

Sioux Camp, c. 1907

Plight of the Plains Indians

The Great Plains and its abundant supply of buffalo, horses, and grasses had supported American Indian groups on the plains, including the Comanche, Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa, and Sioux tribes.The Federal government had increased the number of Indians in the West through relocation to almost a quarter of a million by 1865, adding to the population of Cherokee, Seminole, and Choctaw that had been forcibly moved in 1838 during the Trail of Tears. See the Indians Reservations and Tribes interaction to learn more about where each tribe’s reservation was located.

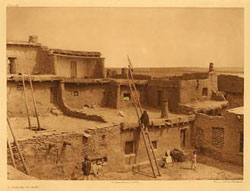

Corner of Zuni adobe houses, c. 1903

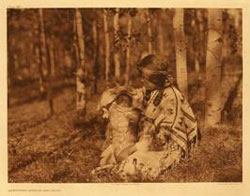

Indian tribes on the plains shared little in common and generalizations are difficult. For example, tribes spoke different languages and had different kinds of lifestyles. Some were nomadic and followed the buffalo, while others were sedentary farmers, developing permanent housing and irrigated farmlands. Tribes might have thousands of members but most subdivided themselves into smaller bands, ruled by councils where most members participated in the decision-making process. Work was often delegated by gender: men hunted and traded and women raised children, gathered fruits and nuts, and prepared meals.

Assiniboin mother and child, c. 1926

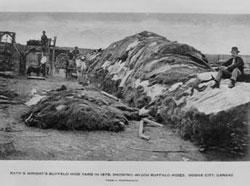

Rath& Wright's buffalo hide yard in 1878, showing 40,000 buffalo hides, Dodge City, Kansas

Indian life on the Plains changed dramatically after the Spanish introduced horses to the plains in the sixteenth century. Prior to this, Indians used dogs to carry supplies. Indians quickly adopted horse-culture, training young males to become proficient hunters and warriors on horseback. With the use of horses came an increased reliance on hunting the buffalo. Tribesman could surround and kill dozens of buffalo while on horseback, a feat not possible in the past when they hunted on foot. Horses enabled tribes to abandon farming and full-time settlements in favor of becoming nomads, roaming the plains in pursuit of the buffalo herds.

Bison ranging, c. 1927

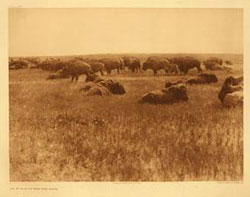

Nearly 30 million buffalo lived on the plains in 1800, providing Indians with a source for food, shelter, and clothing. Natives skinned the buffalo and used the pelts to make clothes, blankets, and tepees. They used the meat for food, drying or smoking it to preserve it for longer periods of time, then crafting tools from the remaining bones. They even used the manure for fuel, burning it to keep warm on cold nights.

By the mid-1800s, buffalo herds were in a perilous state. Overhunting, disease, and eager Eastern manufacturers plummeted the number of buffalo to near extinction. While a buffalo coat and hat represented the height of fashion in New York City, it meant hunger and frustration to an Indian tribe, which fueled conflict between the Natives and migrant settlers on the Plains.

The Indian Wars

Prior to the Civil War, Americans had considered the great western region between the Mississippi River and Rocky Mountains “Indian Territory” and had resettled many tribes from the East Coast to the region in an effort to segregate the races. The Federal government broke treaties signed to grant land in perpetuity as Manifest Destiny gripped the nation and settlers migrated west into the plains and prairies once promised to the Indians. Migration by farmers, ranchers, and miners to the West led to increasing conflicts. Natives fought back, attempting to protect their lands. Although most tribes resisted Anglo migration, the Sioux on the northern plains and Apache in the southwest were noted as fearsome warriors, skilled at mounted warfare.

The Apsaroke on the Little Bighorn, c. 1908

Views on land and ownership

Views on land ownership and the environment caused many conflicts between white settlers and Native Americans. Although tribes varied, Indians generally did not believe that they could “own” the land. Rather, land was held communally and belonged to the entire tribe and was to be protected by the tribe. The plants and animals on the land held spiritual and religious meaning. White settlers took an almost opposite viewpoint, believing that the land, plants, animals, and minerals were created by God specifically to be used by humans. Anglo settlers believed that ownership of the land was crucial and that humans were to be the masters of the environment. This worldview was in direct opposition to the beliefs of the Indians.

Federal Policy

In 1851, Congress approved a new policy toward Native tribes that created a limited and defined boundary within which tribes were to live—the reservation system. The Department of Indian Affairs determined tribal territories, and treaties were signed at Fort Laramie, guaranteeing extensive territory to the northern Plains Tribes in return for promises that the Indians would not harass white settlers. The government proposed to supply the Indians with anything that they could not produce themselves from the reservation land, an offer of $50,000 worth of supplies every year for 50 years. Thenthe government added to this offer of maintenance with a promise that the tribes would have perpetual control and ownership of their reservations and remain sovereign nations on the reservations, residing within the larger United States. Two years later the government secured a similar treaty with southern Plains Tribes, creating a safe corridor of passage for American emigrants through the region.

Boundaries, however, proved hard to patrol, and both white settlers and Indians broke the agreements. Tribes crossed the reservation boundaries to hunt, and white settlers attempted to mine gold on Indian land. Peace did not last, and wars—both conventional and guerilla—broke out between the two groups.

Sand Creek Massacre

Battle of Sand Creek. Painting by Robert Lindneux, State Historical Society of Colorado

After a series of clashes in 1864, Cheyenne and Apache warriors agreed to gather at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado, on a promise of safe passage from the Territorial governor. The gathered Indians—nearly seven hundred in all—were surrounded the morning of November 29, 1864, by Colonel John M. Chivington and his men. Chivington ordered his men to “kill and scalp all, big and little,” and—despite the white flag of truce flying—Chivington and his men killed and then scalped ninety-eight Cheyenne women and children, mutilating their bodies. Afterward, Chivington’s militia corps displayed their scalps in Denver where they were greeted with cheers from white settlers. But the Federal Army was appalled and began to prepare for retaliation from the Natives.

Soon after the massacre, the Plains exploded in warfare as the Lakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne joined forces to seek vengeance, attacking settlers, burning stagecoaches, and looting ranches. By 1866, when the Sioux ambushed and killed Captain William J. Fetterman and seventy-nine of hismen, Civil War hero and commander of the Army in the West William T. Sherman declared, “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women, and children.”

Indian Peace Commission

John Taylor, “Treaty Signing at Medicine Lodge Creek,” 1867. Drawing created for Leslie’s Illustrated Gazette

Chief Joseph of the Nez Pierce

The next year, officials from the Department of the Interior formed a peace delegation in an attempt to the end the wars. The delegation resulted in the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek (1867) that promised reservation land, supplies, and a school in Oklahoma to the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche in return for their relocation away from white settlers. The next year a second treaty was signed with northern tribes, granting them land in South Dakota. It would take the army to coerce the Indians onto the reservations, as many tribes resisted.

The Nez Perce were one of the tribes that resisted relocation. Led by Chief Joseph, the Nez Perce attempted to flee to Canada after the army forced them from their reservation land in Idaho. The Nez Perce eluded the army for three month, traveling north through Montana. More than 200 died along the way. Chief Joseph eventually surrendered on a guarantee that they would be allowed back on their original reservation land in Idaho. Instead, the army sent them to Oklahoma where many of the remaining Nez Perce died. Chief Joseph became an outspoken critic of the government’s Indian reservation policy. The government eventually allowed the Nez Perce to move to a reservation in Washington Territory, but denied their petitions toreturn to their homeland in Oregon.

With more than 2,000 Federal soldiers in pursuit, Chief Joseph led about 800 Nez Perce toward the Canadian Border—and freedom. The tribe outmaneuvered the soldiers, traveling more than 1,700 miles across Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana before surrendering because of exposure-related deaths. Popular legend has attributed these words to Chief Joseph when he surrendered:

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

White encroachment onto Indian lands remained the largest source of conflict. Despite treaties, white settlers swarmedreservation lands and neglected treaty terms, especially in the Black Hills of South Dakota after settlers discovered gold. The Sioux, who lived on a reservation in the Black Hills, protested the invasion of their territory. The government offered to lease the Black Hills or pay $6 million for the land if the Sioux would sell. When they refused, the government offered a “fair price” and attempted to force the Sioux to move, forcing them onto another reservation.

Chief Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull, one of their leaders,argued that “we must stand together or they will kill us separately.” The Indians prepared to fight the army troops. By June of 1876, more than three thousand Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho rendezvoused on the Little Big Horn River and prepared to fight. The battle came when General George A. Custer stumbled across the encampment and was slaughtered along with 250 of his men in the greatest Native victory of the Plains wars.

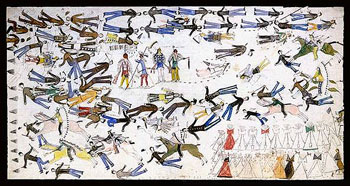

Battle of Little Big Horn from the Indian perspective. By Kicking Bear (MatoWanartaka), c. 1898. Watercolor on muslim.

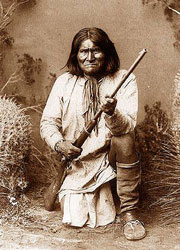

Geronimo , Apache Indian

The victory was short-lived. The army regained its offensive stand and forced the Sioux to give up their hunting grounds and the gold-filled lands on their reservation in return for payments. When this decision was reached, Chief Spotted Tail responded by saying, “Tell your people that since the Great Father [President of the U.S.] promised that we should never be removed, we have been moved five times. . . . I think you had better put the Indians on wheels and you can run them about wherever you wish.”

Geronimo’s capture in 1886 marked the end of much of the conflict. Geronimo, a chief of the Chiricahua Apaches,had fought white encroachment in the southwest for almost 15 years. Only one major incident followed Geronimo’s seizure and it occurred at Wounded Knee.

Ghost Dance

Ghost Dancers

In 1888, Wovoka, a member of the Paiute tribe, became ill. When he recovered he claimed thatin his delirium he had visited the spirit world where he learned that the Native peoples would be rescued by a savior who would restore the land to the Indians. To bring on this savior, argued Wovoka, the Indians had to engage in a ceremonial dance each new moon. The Ghost Dance spread rapidly, attracting a large following on reservations while generating fear in the army, especially after the Sioux took up the dance in 1890. The Sioux danced with such fervor that the army officers on the reservations attempted to outlaw the ceremony, beginning by arresting one of the Indian leaders, Sitting Bull. The attempted arrest ended in Sitting Bull’s death and soon afterward, a bloodbath. On December 29, 1890, a rifle discharged into a group of Indians who had gathered at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, leading to a clash that resulted in the deaths of 200 Indians and 25 soldiers. Wounded Knee was the last significant battle of the Indian Wars.

Shoshone Indians at Fort Washakie, Wyoming Indian Reservation. Some of the Indians are dancing as soldiers are watching, 1892

Indian resistance collapsed after Wounded Knee, due to the eradication of the buffalo as much as Anglo suppression. Western settlers and miners had little tolerance for the “savages,” and the army fortified its western troops, sending the cavalry out to slay warriors, destroy villages, and eradicate the food supply. With a technological superiority that included better weapons, telegraph communications, and railroads, the army sealed the Indians’ fate. The task was made easier by the long-standing antagonisms between tribes. Nations like the Pawnee, Arikara, and Crow eagerly aided the army in subduing their enemies, the Sioux and Cheyenne. Scroll the Wars of the West timeline to see the span of wars and battles that occurred in the West between Indians and Anglos.

Assimilation

Indian children at the Indian Industrial and Training School at Forest Grove, Oregon, c. 1882. This was a boarding school for Indian children

American Indians did not disappear at the end of the 1890s, indeed they carried on and continued to resist in several different ways. Most whites wanted Indians to sell or break up their ancestral lands and become farmers, replicating the traditional Anglo patterns of patriarchy with the men tilling the fields and the women working in the home. Whites wantedNatives to conform to their social and educational standards, including the Christian religion.

This desire to assimilate the Indians into white culture soon became government policy. Ethnocentric reformers included government officials, church leaders, and social workers. These individuals were committed to forcing the Natives to “walk the white man’s road,” as Sitting Bull had once called it.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs led this campaign for the government, carrying out a program of assimilation for Indian children by establishing boarding schools that displaced them from their parents. The government removed children as young as 5, forcing them to learn English, dress in Anglo clothing, and practice Christianity. The children were told to abandon their old ways, in the words of one reformer, to “kill the Indian and save the man.” See what assimilation looked like for one group of Apache children who attended boarding school in the Extreme Makeover interaction.

“The Reason of the Indian Outbreak,” 1890.Political cartoon that satirized the corruption of federal agents in charge of western Indian reservations. Officials pocketed most of the federal money meant for the Indians

But land reform proved to be the pivotal component of the government’s assimilation program. In 1887, Congress enacted the Dawes Severalty Act to force the assimilation of American Indians into what they perceived as the mainstream of national life. The act attacked the tribal autonomy and communal spirit of the American Indians, or what Dawes called their “tribalism.” The Act allotted each head of an Indian household 160 acres (80 acres for single adults and 40 acres for minors), or 320 acres if the land was suitable only for grazing. Once the land set aside for the tribe had been divided among the Indians, any remainder would be sold to the public. The Dawes Act, with the goal of turning American Indians into stockmen and farmers like Anglos, failed miserably.

Reformers failed to achieve their stated goals, and tribes suffered at the hands of grafters who assigned the most arid lands to Indians and sold the best patches to white settlers. Natives often placed their lands in the hands of white “guardians” who then stole the land from them to resell. Indian land holdings dropped from 155 million acres in 1881 to only 77 million acres 20 years later. See the interactive map on Loss of Indian Land to see the drop in Indian land holdings.