New South Beginnings

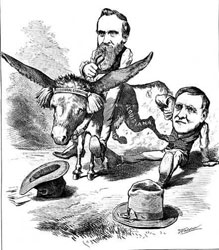

Political cartoon from the New York Daily Graphic, February 26, 1877, showing Hayes as the winner in the disputed 1876 election.

The New South began to emerge almost as soon as the remaining federal troops were removed from the South in 1877 and continued well into the twentieth century.

Compromise of 1877

In the Compromise of 1877, Democrats and Republicans came to an agreement regarding the future of the southern states. Republican party leaders promised to remove the last remaining Union troops from the region if Democrats from the South allowed Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to win the presidency after the disputed 1876 election. By this agreement a southerner would be admitted to the cabinet, monies would be made available for internal improvements, and the process of elections would be left up to the southern states. The Compromise of 1877 allowed a take-over of the last remaining southern state governments by Democrats, ending the nation’s experiment with a federally inspired Reconstruction that had provided new state constitutions, public education, and the protection of voting rights for freedmen.

The Redeemers

Men and women weaving in the White Oak Mill in Greensboro, North Carolina, 1909. Photo from the National Museum of American History.

By the 1880s, a Democratic majority reigned in every southern state, and southerners called it Redemption. The new Democratic office holders were known as Redeemers because they redeemed the South from federal intervention. For the most part, these New South leaders came from the middle classes. They were lawyers, businessmen, and industrialists, while a few were planters with large estates. Most had served the Confederacy, and thus they cashed in on their military service and their loyalty to the Lost Cause.

Redeemers were interested in increasing economic opportunities for southern businessmen and industrialists and maintaining a docile black labor for for agriculture. As governors and legislators, they worked to keep taxes low, and encouraged the building of railroads, textile mills, tobacco factories, steel plants, lumber industries, and coal and phosphate mining companies, and promised a labor force that would accept low wages. The legislators offered generous land grants and tax reductions to companies that would locate in the South or to southern capitalists who wanted to start up industries. They did not spend as much effort on improving the economic condition of farmers, although they did help large landowners with laws to keep sharecroppers working on the land.

Redeemers and State Governments

Harper’s Weekly cartoon by Thomas Nast showing the fate of African Americans in the South.

Redeemers re-crafted state constitutions, lowered taxes on land, and cut expenses wherever they could, underfunding such important endeavors as public education as well as state supported institutions for the blind, deaf, and mentally challenged. Redeemers cleverly gained power by railing against the “excesses” of the Republican dominated Reconstruction governments (1867-1877), running racist campaigns, touting the virtues of white supremacy, and by establishing the Democratic party as a closed corporation where positions were passed around and party regulars continued in office year after year. Dissenters were kicked out and loyalty was rewarded. They controlled black voters after 1882 by instituting measures such as the eight box ballot law, which meant voters had to place as many as eight ballots in the correct boxes, one for each office. This process served as a form of literacy test for illiterate white voters and for black voters who had been denied the right to learn to read as slaves. In some states, Redeemers gave the power of appointment of local officials to the state legislatures, working against democracy and forging the “Solid South”- the idea that the Democratic Party dominated all the Southern states. Their control over state politics would not be seriously challenged until the 1890s, when the reform-minded Populist movement rose up in opposition to Redeemer rule.

Georgia as an Example

Georgia presents a good example for understanding the machinations of the Redeemers and their followers. A famous political group emerged in 1872 called the Bourbon Triumvirate. Alfred H. Colquitt won the governorship from 1876 to 1882; he was followed by John B. Gordon from 1886 to 1890. Their colleague Joseph Brown remained U.S. senator from 1880 to 1890. Together three men held a near lock on Georgia politics and followed the typical Redeemer agenda of low taxes and a heavy emphasis on attracting industry, such as railroads and coal mining. Although insisting on minimal state services, including public education, during their tenure the state legislature spent $1 million dollars building an impressive state capitol. They also endorsed the institution of convict labor (a disproportionate number were African American), which had begun in Georgia in 1868. Under the convict lease system, prisoners were hired out by the state to industrialists who used their brawn to construct railroads, work in the mines, or even to build state capitols. There were almost no safeguards for the convicts; the legislature in an attempt to reform the worst of the abuses passed a law allowing only one person per work site to administer whippings. States across the South adopted the convict lease system, arguing that it provided prisoner control, reduced the state’s costs by avoiding building penitentiaries, and provided income. Its abuses became notorious and would be addressed by future reformers, many of whom were women.

Alfred H. Colquitt |

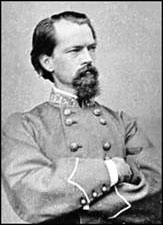

John B. Gordon |

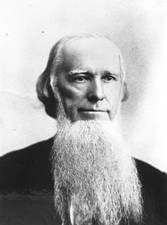

Joseph Brown |