Reconstruction in the South

Carpetbaggers and Scalawags

Cartoon of carpetbaggers heading South after the war

Among those eligible to hold office in the South were freedmen and Union supporters, either native white southerners or northerners who came to the South to begin businesses or eventually to enter politics. Known as “Scalawags” and “Carpetbaggers,” Republican whites in the South made up the majority of the states’ assemblies during Congressional Reconstruction. Both groups of whites were well educated and from the middle class. Many were lawyers, businessmen, teachers, newspaper editors, and veterans of the Union Army. Northern Republicans who lived in the South, known as Carpetbaggers, comprised no more than 2 percent of the population. Native-born white Republicans, known as Scalawags, were more numerous but suffered the disgrace of turning traitor to their region and to the Confederate cause. They constituted a majority of the Reconstruction governments in Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Texas. Scalawag and Carpetbagger interests rested with revitalizing the South and bringing industry and ingenuity to southern economic life. They saw their alliance with freedmen as a matter of convenience, yet they were willing to defend the rights of freedpeople to civil equality.

This contrasting group of political allies created the Reconstruction state constitutions and governments that stayed in power from 1867 to the 1870s. They wrote constitutions that modernized southern states and added provisions long established in the North. Most Reconstruction governments in the South instituted taxes on land, to which white southern landowners were unaccustomed. Antebellum legislatures had employed head taxes, but land taxes relieved poorer taxpayers. The Reconstruction constitutions eliminated black codes, imprisonment for debt, and revamped the penalties for capital punishment. They rebuilt southern bridges, roads, and harbors, especially those damaged by the war. They invested funds in orphanages, institutions for the blind, deaf, and mentally handicapped and rewrote constitutions to include divorce (all except South Carolina) and married women’s property rights. Perhaps the most important addition to southern life was the institution of public education in every southern state. Each state adopted segregated public education, but in many cases this was the first time any state- supported schooling existed. The result was a bounty for African Americans who flocked to schools. By 1877, 600,000 children attended public schools in the South.

The Freedpeople

Photograph of freemen at Fort Donelson after the war

White southerners of all classes loyal to the Confederacy first reacted to defeat with shock and anger. But while white southerners stewed with indignation, African Americans rejoiced. Viewing their position from a completely different perspective, freed slaves saw the Civil War as their “Freedom War” and equated it with the Israelites’ escape from slavery in Egypt. They saw themselves following Moses, crossing the Red Sea, and traveling toward the Promised Land. No such miracles actually occurred for freedpeople. In fact, the route from slavery to freedom was perilous, uncertain, and filled with hard work.

Photograph of freed family after the war

Eventually, most freedpeople left the old homestead of their former owners. Some traveled to find lost loved ones; others went in search of jobs in towns or to find land to farm. Between 1860 and 1870 blacks that owned land increased from less than 1 percent to 20 percent. Many freedpeople married, an institution that had been denied legally to them while in bondage. By marrying, they established households and were more likely to keep their children from the apprenticeship system. Between 1865 and 1867, many southern courts assumed that African American parents were unfit to care for their children and under Black Codes ordered the removal of black children to white families—sometimes their former owners. They were to remain in the apprenticeship system until age twenty-one. To many this smacked of re-enslavement, and apprenticeships declined with Congressional Reconstruction beginning in 1867.

Sharecropping

Many freedpeople ended up working for white landowners, some of whom were their former masters. But they avoided living in the old slave quarters, working in gangs, or making contracts that seemed to limit their independence. This led to a land - labor system peculiar to the South. White landowners who had owned slaves had too much land to work themselves. The majority of freedpeople, constituting a sizable labor force, owned no land. In a cash-poor economy whites and blacks worked out a system of sharecropping where the owner divided the land into parcels of usually thirty acres, built a house (often just a cabin) for black family members, and supplied them with provisions such as seeds, fertilizer, even a mule, harness, and a plow to get started. The owners insisted on dividing the crop between “the cropper” and himself, usually at 50 percent.

Photograph of a 13 year old boy sharecropping in 1937

At first sharecropping worked well for blacks, and overall their incomes rose. This came even though African American farmers worked fewer hours than they had as slaves and wives stayed home to care for children, only occasionally working in the fields. But over time, cotton prices declined due to a worldwide cotton glut, and sharecroppers found they needed to borrow money to buy supplies. They often took out loans against their future crop and at the end of the year paid off their debt when they sold their cotton. High interest rates, fraud, or sometimes crop failures could leave a family in debt year after year and southern states passed laws that made it a crime to leave the land until the debts were paid. This system tied many freedpeople to the land, to sharecropping, and to poverty.

Communities

Photograph of freed family after the war

Despite the economic setback for many farmers, freedpeople created their own communities after the war. They established churches, schools, and annual emancipation celebrations. They joined the Republican Party, held conventions, and voted in state and national elections for the first time. They sought independence from white dominance and violence.

While many founded small communities in the countryside, others lived in black sections of towns either by choice or because of discrimination. They joined established denominations such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), AME Zion, or the National Baptist Convention. They built churches, hired their own preachers, started Sunday Schools, and worshipped with enthusiasm. Churches were centers of political activity and community awareness, and black preachers were respected members of the community.

Each year, freedpeople celebrated their emancipation with ceremonies, parades, programs, barbecues, and feasts that honored ex-slaves and Union soldiers. In Texas, slaves first heard of their freedom on June 19, 1865—today known as Juneteenth Day—and annual celebrations followed each year. In Washington D.C. freedpeople celebrated their emancipation on April 16 because slaves there had been freed in 1862. But the majority of former slaves across the South celebrated on January 1, the day the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in 1863.

Education

Schooling was exceedingly important to freedpeople, and students from five to seventy walked to one-room schools to learn to read. Schoolteachers from the North—most of them women—came during the early years of Reconstruction to work in 1,000 Freedmen’s Bureau schools or in schools established by the American Missionary Association and by northern denominations. Eventually, black teachers took over the schools. Thirteen colleges opened for blacks in the South and in 1880 over one thousand former slaves graduated from these colleges before 1900. Many of these new graduates filled the need for black schoolteachers in the South.

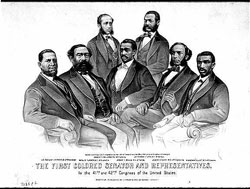

Illustration of the first African Americans to serve as U.S. Senators and Representatives

Political Activism

Southern blacks actively worked to shape the nature and direction of Reconstruction. Although most freedmen found themselves destitute after the war, many believed that the promise of freedom gave them a new sense of direction. They moved into politics, formed Union Leagues, joined the Republican Party and voted and held office for the first time. Several hundred African American delegates attended state constitutional conventions. About 600 blacks, most former slaves, served as state legislators. The majority of the 2,000 black office holders were men who had achieved an education in northern or European schools. They were often the sons of white planters and slave mothers who were raised as legitimate heirs. Francis L. Cardozo, South Carolina Secretary of State, was such a person, whereas U.S. Senator Hiram Revels from Mississippi was the son of free blacks. During Congressional Reconstruction fourteen African Americans from the South served in the House of Representatives and two in the Senate. No black man was elected governor and only a few served as judges. P.B.S Pinchback of Louisiana served as acting governor for a while, but African Americans served in every state legislature, and in South Carolina they comprised a majority for two years. Black office holders helped to create the new state constitutions and helped govern southern states during Reconstruction.