Congressional or Radical Reconstruction, 1867-1877

Radical Republicans won a victory in the 1866 mid-term elections when Americans voted a huge Republican majority into Congress, capturing a two-thirds majority in both houses. The new Republican majority decided that Congress, not the president, should control the course of Reconstruction. Congress refused to admit the states that had enacted governments under Johnson’s plan and then proceeded to place the entire South under military rule. In March 1867 Congress passed, over President Johnson’s veto, several Reconstruction acts. The First Reconstruction Act, also known as the Military Reconstruction Act, effectively raised the qualifications for southern states’ readmission to the Union.

The Military Reconstruction Act, 1867

- Congress placed the former Confederate states under military authority and divided the states into five districts with a Union general in charge of each district. The United States Army became the government in these districts until such time as new governments were constituted.

- Congress charged the former Confederate states with creating new state constitutions and new governments. The military directed the registration of voting for all adult males including African American males who swore they were qualified.

- Congress asserted its right to reframe the state governments and constitutions, and the Supreme Court upheld this curtailment of state power in the courtcase, Texas v. White (1869).

- Congress demanded that all the new state governments disfranchise high-ranking Confederates.

- Congress demanded that all new state governments ratify the Fourteenth Amendment.

If the states fulfilled these requirements, they would be readmitted to the Union. During the spring and summer of 1868, with blacks voting in large numbers, seven of the former Confederate states (North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Arkansas, and Louisiana) completed the requirements and were reseated in the Union. In 1870 Texas, Mississippi, and Virginia also fulfilled the requirements, after ratifying the Fifteenth Amendment.

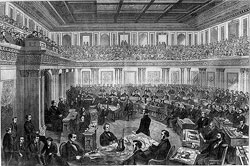

Illustration of Johnson’s impeachment proceedings from Harper’s Weekly, April 11, 1868

Did you know...

Most historians believe that the charges against Johnson were spurious and motivated by Radical Republican political maneuvering.

Removing a President from power involves two steps. First, the House of Representatives much impeach (formally accuse) a president. Secondly, the Senate must hold a trial and vote to convict. President Bill Clinton and President Andrew Johnson are the only presidents to have been impeached by the House of Representatives. The Senate acquitted both presidents.

Although President Johnson vetoed the Reconstruction Acts, he reluctantly played the role of commander-in-chief and appointed military governors to the southern states. But Johnson balked at the other acts Congress passed in 1867. One, the Tenure of Office Act, required Senate approval before the president could remove cabinet officials or other officers whose appointment the Senate had originally confirmed. The other, the Command of the Army Act, limited the president’s authority by allowing him to issue military orders only through the commanding general, who at the time was Ulysses S. Grant. While Congress was in recess in August 1867, Johnson attempted to replace Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton without Senate approval. Stanton refused to resign, and when Congress returned, it initiated impeachment proceedings. In truth, Congress was disgusted with Johnson’s behavior. He continued to pardon ex-Confederates, he removed military commanders who were sympathetic to the equality of African Americans, he stated that “white men alone must manage the South,” and he used vitriolic language against the Joint Congressional Committee. He spoke frequently to the nation, venting his contempt for Congress to his audiences while upholding the principle of white supremacy. Congress had had enough, and they used the violation of the Tenure of Office Act to bring impeachment proceedings. The trial began in March 1868 and at the end of three months, Johnson was saved from conviction by one vote. After the impeachment trial, Congress took over complete control of Reconstruction.