A child’s appeal

Abolitionism

The abolitionist movement of the antebellum era of American history produced some of the most dedicated reformers in American history, men and women who shook the nation to its foundation and challenged its fundamental assumptions concerning race, equality, and human rights. A product of a broader, massive campaign to reform American society, the movement focused on slavery as the ultimate sin and called on America to live up to its Revolutionary ideology. Basing their demands on spiritual appeals of evangelical Christianity and the secularism of Enlightenment philosophy, the abolitionists established an important heritage for later generations of activists, developing tactics and methods, as well as principles, for future campaigns for human dignity.

Anti-Slavery Quakers

John Woolman preaching

During the colonial era, the Society of Friends, the radical Protestant sect better known as Quakers, issued the first challenge to slavery based on moral and religious grounds. Challenging traditional assumptions of mankind’s evil nature, the Quakers emphasized the inherent dignity of the individual, human equality, and each person’s capacity for goodness. The essence of Quaker theology was the Doctrine of Inner Light, the belief that God endowed each person with the capacity to know Him without the intercession of church authority. Since no person had the right to exercise absolute power over another, they opposed violence and physical coercion and believed in universal brotherhood and God’s universal love. The precepts of their religion formed the basis for later defenses of human rights and equality.

The first Quaker spokesmen to take antislavery to the public at large were John Woolman and Anthony Bezenet. They worked with individual slaveholders, teaching that slavery violated the golden rule and corrupted both slave and slaveholder. Only the illegitimate abuse of power prevented the Negro from developing talents and abilities that he possessed in full measure with whites. When freed, argued Woolman and Bezenet, slaves must be granted full equality and compensated for their years in subjugation. A later generation of abolitionists returned to the positions and rationales carved out by these early religious advocates.

The American Revolution and Slavery

Slave sitting alongside a New York harbor

By challenging traditional assumptions about political power and social hierarchy, the Revolutionary movement led inevitably to questioning the justice and necessity of slavery. When the Englishman Dr. Samuel Johnson asked, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?” the Americans did not need his insults to remind them of slavery’s inconsistency with their heroic stand for liberty and self-government. They must have pondered, if discontented colonists could resort to violence to overthrow imperial might, could slaves overthrow their masters?

Prominent American Revolutionaries inveighed against the injustice of slavery and at times seemed disposed to act on their convictions. James Otis declared it a “shocking violation of the law of nature” that enabled slaveholders to “barter away other men’s liberty.” In his original draft of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson condemned the king for the slave trade in no uncertain terms, declaring that he had “waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people [Africans] who never offended him captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.” In later writings, Jefferson declared, “The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submission of the other,” and warned, “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; and his justice cannot sleep forever. . . . The almighty has no attributes which can take sides with us in such a contest.” Other Southern slaveholders such as Patrick Henry and James Madison condemned the institution for its violation of natural rights, while Northern leaders such as Alexander Hamilton, Albert Gallatin, and Benjamin Franklin became active in antislavery efforts.

Nor were the lessons of the Revolution lost on black Americans, as they asserted their rights, resisted their oppression, and chose the course of action most likely to lead to liberty for them. In Virginia when Lord Dunmore offered freedom to those who joined the British army, hundreds deserted their masters and fought for the Empire. During the course of the war, an estimated 20,000 joined the British cause. In the North, some legislatures granted freedom to those who fought for the Patriot cause. Politicized by Revolutionary rhetoric, Northern black communities came together in opposition to slavery and in support of each other. For example, New England slaves petitioned for emancipation, declaring that, “The divine spirit of freedom seems to fire every human heart on this continent.”

Following the Revolution, concerns with securing the union and establishing order took precedence over the Revolutionary goals of liberty and individual rights. Even if delegates had the will, the Confederation Congress lacked any power to address slavery on a national scale, but as Western lands were surrendered to national authority, Congress did consider the issue of the institution’s expansion, giving the young Republic one last chance to act in behalf of freedom. In 1784, Jefferson introduced a bill to prohibit the spread of slavery throughout the western territories, but the bill failed by one vote, and three years later the Northwest Ordinance prohibited it only north of the Ohio River.

American Colonization Society (ACS)

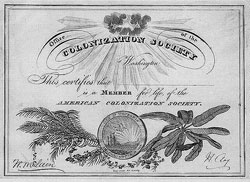

Life membership certificate for joining the American Colonization Society

Motivated by the apparent emergence of militancy among free blacks as well as by the desire to fulfill America’s promise, the ACS had broad appeal. As one of the Society’s missionaries explained, “We must save the Negro or the Negro will ruin us.” Based on the plan of Robert Finley, a New Jersey schoolteacher, the ASC seemed to offer something for everyone. America could fulfill its promise for a free and equal society, blacks could achieve freedom and equality in Africa, the threat of race violence would be solved, and Christianity and civilization would be transported to Africa along with the former slaves. In the Upper South slaveholder Senator Henry Clay became the strongest supporter of government funding for the organization, while in Virginia such notables as James Madison, James Monroe, and John Marshall signed on. In the North future abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, James Birney, Gerrit Smith, Arthur Tappan, and Salmon Chase, among others, believed the ASC offered the best hope for overcoming the prejudice that stood in the way of emancipation.

In 1822 the ACS purchased land in West Africa from local chieftains and founded the colony that came to be known as Liberia. Never having a realistic possibility of achieving its goals, it colonized only about 15,000 blacks in Africa, making no dent in either the slave or free black population and certainly not keeping pace with the natural increase of blacks in America. By the 1830s it was apparent that government financing would not be forthcoming, planters from the Lower South had begun to suspect the organization’s antislavery goals, and Northern reformers were turning against it, largely because of organized black resistance.

Meanwhile a combination of events internationally, nationally, and locally inspired a dramatic shift in American antislavery activities. Abroad, a slave rebellion in Jamaica had contributed ammunition to British antislavery advocates’ demand for immediate abolition. In 1833 when the movement accomplished emancipation throughout the British Empire, American abolitionists, who always had strong ties with the British movement, took hope that they could follow their friends’ example. At home increasing frustration with the futility of the ASC’s mission meant that genuine reformers were seeking a more meaningful approach. Most important, Northern free blacks’ opposition to colonization and their demands for justice were finally getting an audience among white abolitionists. In addition, an emotional religious revival, the Second Great Awakening, was creating a receptive Northern audience for a more radical message.

Turning Point

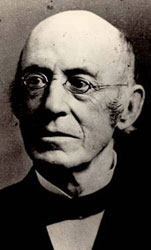

William Lloyd Garrison

The turning point in the antislavery crusade came in 1831 with the demand for immediate abolition, without colonization or compensation. William Lloyd Garrison, with the support of Isaac Knapp and Stephen Foster and the financial aid of Arthur Tappan, provided the catalyst for this phase of the movement when he published the first issue of the Liberator. From the beginning, no one could doubt Garrison’s commitment or agenda:

Just twenty-five years old, Garrison had written his first challenge to slavery three years earlier. Like many northern reformers, he had first associated with the ACS and then joined Benjamin Lundy in Baltimore to write for the Genius of Universal Emancipation, which was dedicated to the cause of gradual emancipation. Already noted for the vehemence of his language, Garrison had served a stint in the Baltimore jail for libel. Then upon his return to Boston, he found the black community adamant in its opposition to colonization, and his association with that community now helped formulate his philosophy for immediate emancipation. Although Garrison opposed the violent overtones of Walker’s Appeal, he admired its exposure of racism and its pernicious effects. From the beginning of his crusade when the black philanthropist James Forten sent him $54.00 in advance for subscriptions, Northern blacks were Garrison’s primary audience. It was with their commitment and help that he was able to launch the Liberator.I am aware, that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which I has fallen;—but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.

Garrison’s call for “immediate, unconditional, uncompensated emancipation” was the opening volley in a new phase for American abolition. Garrison joined his condemnation of the institution with a clarion call for full racial equality, insisting that any perceived inferiority of blacks was the result of slavery and discrimination. His tactic, “moral suasion,” assumed that when slavery was exposed as the crime against humanity it was, when slaveholders were universally condemned as criminals, and when the justice of black freedom and equality became apparent, not only would slavery end but America would emerge committed to liberty and justice for every person. Attacking both colonization and gradualism as compromises with sin, Garrison insisted that he could no more call for a gradual end to slavery than for gradual reform of a thief or murderer. His language, with its uncompromising demands, was calculated to disrupt and disturb, to draw attention to the crusade, and to arouse a nation whose conscience had been dulled by sin. Garrison’s career reflected the influence of both radical religion and Enlightenment ideology, as he called upon his audiences to heed the will of God and to fulfill the promise of the Revolution.

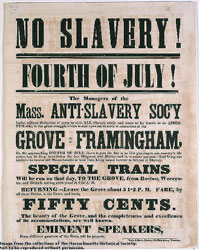

broadside advertising an Anti-Slavery rally on the fourth of July

What Garrison called for was a nothing less that a complete moral revolution. His readership was never large, and he offered no specific plans for achieving his goals, but according to his biographer Henry Mayer, Garrison “inspired two generations of activists—female, male, black and white—and together they built a social movement which, like the civil rights movement of our own day, was a collaboration of ordinary people, stirred by injustice and committed to each other, who achieved a social change that conventional wisdom first condemned and then ridiculed as impossible.”

Abolitionists’ aspirations for immediately converting the nation, even the slaveholding South, to principles of justice and equality proved hopelessly naïve. Rather than accepting abolitionists’ principles and freeing their slaves, or even listening politely, the majority in both the North and South responded with intense hostility and seemed determined to silence the abolitionists. In the North, antislavery agents were frequent targets of mob violence that prevented their speaking and sometimes threatened their lives and liberty. All of the antislavery agents faced hostile audiences who booed and hissed them, pelted them with eggs or stones, and denied them a forum for their lectures. Mobs destroyed antislavery presses, sacked the homes of abolitionists, and burned buildings that had allowed abolitionist meetings. In 1835 Garrison was seized by a mob, dragged through the streets and threatened with lynching. Only by jailing him overnight was he rescued. In 1837 Elijah Lovejoy, an abolitionist editor in Alton, Illinois, died defending his press, after mobs had already destroyed two of his presses.

William Lloyd Garrison published The Liberator, a Boston-based Abolitionist newspaper, from 1831-1865. He advocated the immediate release of all slaves and the extension to them of complete legal and political equality-a radical idea at the time. Read excerpts from The Liberator by rolling over the news paper.

Charles Sumner

But the violent resistance to the abolitionists’ crusade had unintended results. Instead of frightening them into submission it solidified their determination, proved the righteousness of their cause, and enabled them to tie antislavery to the cause of such fundamental rights as freedom of speech, right to assemble, freedom of press, and right to petition the government. Each time a Northern mob lashed out in violence or Southerners made hysterical demands for repressive measures, abolitionists’ ranks grew. More importantly, a significant number of Northern whites began to view the South as the aggressor and to fear that their own freedom was not secure. The rhetoric of antislavery began to shift to appeals to defend civil rights. As Charles Sumner, who later became a Massachusetts Senator, noted, “We are becoming abolitionists at the North fast; riots, the attempts to abridge freedom of discussion, and the conduct of the South generally have caused many to think favorable of immediate emancipation who have never before been inclined to it.”

In pre-Civil War America, the abolitionists looked beyond the racist assumptions of their generation and challenged America to live up to its ideals. Their incredible energy and commitment meant that the nation could not ignore slavery and that even mainstream, moderate politicians like Abraham Lincoln must ultimately admit that the America could not continue permanently half slave and half free. Americans, North and South, would have to face the reality of slavery and either defend it or oppose it. While the abolitionists failed to achieve the moral revolution they sought and while America did not commit to racial equality until well into the next century, this group of reformers in their time had set precedents, formulated ideologies, developed tactics, and created role models for future generations of human rights activists.