Jackson’s Indian Policy

John Ross, the elected leader of the Cherokee. He would not approve the Treaty of Echota

For Native Americans of the Northwest Territory, the early national era was a time of tragic loss and cultural decline. Alcoholism spread rapidly, and “treaty chiefs” now replaced warriors as tribal leaders. As their land holdings became smaller and the game diminished, the men had little incentive to hunt and had to depend on annuity payments from the United States government. Recognizing that American settlers would likely take their land no matter what course they followed, some of the treaty chiefs tried to drive the best bargains possible under the circumstances, alienating millions of acres of land for small annuities and pennies an acre. Others were guilty of fraud against their own people. As governor of the Northwest Territory, William Henry Harrison had not controlled settlers’ wanton attacks on Indians, acknowledging that frontier whites “consider the murdering of the Indians in the highest degree meritorious.” Nor was Harrison meticulous in determining whether those willing to sell tribal lands actually had any authority act in behalf of a specific tribe. As a result, agreements of doubtful validity were accepted as legitimate, voluntary transfers of property rights.

Early American presidents from Washington to John Quincy Adams held this expansionist vision of America’s destiny. Included in their vision was the obligation to “civilize” the Native Americans by forcing them to give up their “savage” ways and adopt the lifestyle of the whites. In the name of philanthropy and humanitarianism, they proposed the extinction of Native American cultures and laid the basis for United States Indian policy for over a century. To be sure, when Indians clung to their traditional ways, the nation stood ready to mete out harsh punishments, but if they cooperated and ceased being Indians they could ultimately be incorporated into the body politic. If they could not adopt civilized practices as quickly as white settlement expanded, then they must relocate in the West where they would be accorded a longer period of adjustment. As president, Thomas Jefferson first articulated the broad outline for Indian/white relations. With a curious mixture of philanthropy and cruelty, he planted the seeds of what one historian has labeled, the “seeds of extinction” of Native culture. As Jefferson explained in 1803:

“In this way our settlements will gradually circumscribe and approach the Indians and they will in time either incorporate with us as citizens of the United States or remove beyond the Mississippi. The former is certainly the termination of their history most happy for themselves, but, in the whole course of this, it is essential to cultivate their love. As to their fear, we presume that our strength and their weakness is now so visible that they must see we have only to shut our hand to crush them, and that all our liberalities to them proceed from motives of pure humanity only.”

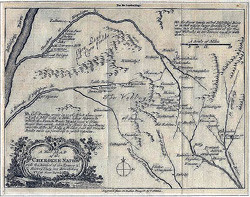

A 1760 map of the Cherokee Nation by Thomas Kitchin

Indian Removal

Until the administration of Andrew Jackson, proposals for Indian removal were based on the assumption that Indians would go voluntarily or be absorbed by American society. In 1830 the issue of Indian removal became official with the passage of the Indian Removal Act.

Native Americans developed varying strategies for dealing with the encroachment of white settlers. Accommodationists and nativists stood together on the issue of retaining all of their remaining territory. Leaders like John Ross, who became Principal Chief of the Cherokee in 1828, were convinced that the only effective way to protect their landholdings and thus maintain their identity was by making modernist accommodations. Some who remained traditional in their beliefs made superficial accommodations as a way to protect themselves and their lands. Regardless of their position on modernism versus tradition, most Cherokee who remained east of the Mississippi in the 1820s agreed that no more land could be alienated without destroying the integrity of the people. Thus the Cherokee republic made unauthorized land sales a capital crime and declared that it was “the fixed and unalterable determination of this nation never again to cede one foot more of land.” In the post War of 1812 era, those who had adopted white ways challenged one basis for Indian removal. For example, that “savages” could not live among “civilized” societies, posing an important question: Once Indians had adopted “civilization were they still subject to removal?”

When Andrew Jackson became president a crisis was already brewing concerning the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole—the Five Civilized Tribes of the Old Southwest. Rather than convincing whites that they had indeed become civilized and thus entitled to remain on their homelands, their prosperous farms merely made their property more attractive and led to even more adamant demands for appropriation. Southern states demanded that the federal government abrogate all treaties with Indians and extinguish all Indian land titles. The governor of Georgia described treaties as “expedients by which ignorant, intractable and savage people were induced without bloodshed to yield up what civilized people had the right to possess by virtue of [the] command of the Creator.” It soon became apparent that the state of Georgia made no distinction between “civilized” and “savage” Indians, insisting that all must leave the state and make their lands available to white settlers. With the discovery of gold on Indian lands in the state, pressure for removal became even more intense.

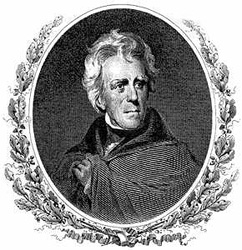

With Jackson’s election Southern states had a champion in the White House. After all, he had become a national hero through his military exploits against Native Americans, as well as against the British, and had already been responsible for the cession of millions of acres of Indian lands. Jackson was motivated not only by his view of Native savagery but also by his belief in states rights and by political considerations. To organize and unite the Democratic Party he needed Southern support, which he could best secure by supporting states rights and Indian removal. The goal of his military campaigns had been to secure the future of the Republic, and he believed that Indian autonomy within the Union threatened the security of the Republic. He also justified Indian removal on the grounds that it was the only way to ensure the survival of the tribes. So determined were white settlers to take control of Indian lands that they seemed likely to annihilate those who stood in their way. Defending Indian interests within the Union seemed an impossible task to Jackson, one that at any rate was not worth its costs in lives or money. Indians must be removed for their own safety, he insisted. He had no patience for those who spoke and wrote in defense of Indians. His annual message to Congress in 1830 made his position clear:

“Humanity has often wept over the fate of the aborigines of this country, and Philanthropy has been long busily employed in devising means to avert it, but its progress has never for a moment been arrested, and one by one have many powerful tribes disappeared from the earth. . . . Nor is there anything in this which, upon a comprehensive view of the general interests of the human race, is to be regretted. Philanthropy could not wish to see this continent restored to the condition in which it was found by our forefathers. What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns and prosperous farms, embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization and religion?”

He concluded that it was “therefore, a duty which this Government owes to the new States to extinguish as soon as possible the Indian title to all lands which Congresses themselves have included in their limits.”

Andrew Jackson

With Jackson clearly on the side of the Southern states, Georgia proceeded to adopt an agenda that ensured final victory over the Five Civilized Tribes. The state legislature moved quickly to abolish the Cherokee government, making it illegal for the National Council to meet except for the purpose of ceding lands, which was illegal under Cherokee law. Because Indians were forbidden to testify against whites, defending their claims became impossible. The remaining 6,000 square miles of Indian lands were to be seized, divided into gold lots and land lots, and distributed to white settlers by lottery. Any Indian who resisted the seizure of his property was to be imprisoned, and “influenc[ing] another not to emigrate to the west” became a criminal offense. Similar laws were soon passed in Mississippi and Alabama. State laws now blatantly abrogated all preceding federal treaties. Meanwhile, in 1830 under Jackson’s influence Congress enacted the Indian Removal Act. For the first time, resettlement in Indian territory became compulsory, but Jackson offered assurance that, “There your white brothers will not trouble you, they will have no claims to the land, and you can live upon it, you and all your children, as long as the grass grows or the water runs, in peace and plenty.”

The Cherokee mounted the most famous resistance to Indian removal, appealing to the national government to protect them from the rapacity of state officials. Their well-educated, mixed-blood leader, John Ross, took their case to Washington, D.C. where he found support for the Native cause among anti-Jackson men in Congress. Having been with the Cherokee regiment that aided Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, he hoped for a friendly reception from the President, but his plea was rejected. Government officials would do nothing to protect Indians unless they agreed to move west.

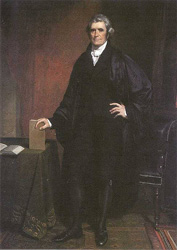

Chief Justice John Marshall

The Cherokee were given renewed hope when their case came before the United States Supreme Court. Two missionaries working under the jurisdiction of the Cherokee nation refused to register and swear loyalty as required under Georgia law. When they were arrested and imprisoned, suit was filed to determine whether national or state law prevailed with regard to Indian relations. Chief Justice John Marshall declared Georgia’s law unconstitutional, ruling that the Cherokee nation was “a distinct community, occupying its own territory with boundaries accurately described” and that Georgians had “no right to enter, but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves, or in conformity with the treaties and with the acts of Congress.” Unfortunately, the Supreme Court lacked the power to enforce its ruling unless the president upheld the law. Jackson allegedly declared, “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it” and encouraged Georgia to proceed with land confiscations.

An 1854 map with the Indian Territory highlighted

Even before the national government could make arrangements for removal, Georgia implemented the lottery system, awarding Indian homes and farmlands when the occupants had no place to go. Suffering the same fate as his less prosperous neighbors, John Ross lost his plantation and his profitable ferry business. Determined to take possession immediately before greater resistance could be mounted, white settlers raided and looted Indian homes, burned their fields, and stole or slaughtered their livestock. Sinking into despair, even those not yet dispossessed were reluctant to plant crops because they realized how tenuous their situation had become. A once prosperous people were quickly reduced to abject poverty.

Meanwhile government promises of a land exchange in Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma) proved difficult to fulfill since those lands were hardly vacant. Original occupants had already been faced with accommodating thousands of migrants who had left the East voluntarily. In some cases, nativist factions, seeking to separate themselves from the influences of the whites, had migrated years earlier and now feared the influence of the new arrivals. Others feared their own land claims would be diminished. For example, Western Cherokee, migrants from years earlier, claimed all of the treaty lands and were hesitant to accept their now impoverished Eastern relatives. Under immense pressure, the number of those willing to remain in Georgia began dwindling as more and more took their chances in the West. By 1835 a core group of about 17,000 Cherokee held on in the East against incredible odds.

John Ridge, son of The Ridge. Ridge was assassinated in 1839 for signing the Treaty of New Echota

While most of these holdouts remained steadfastly opposed to removal, by the mid-1830s a “Treaty Party” led by Major Ridge, his son John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot, editor of the Cherokee newspaper had emerged. Viewed either as martyred heroes who acted to save their people from extinction or as villains who sold out to white pressure and bribes, these men decided that further resistance was futile and that only emigration could save the Cherokee nation. Their secret negotiations with Jackson’s administration resulted in the Treaty of Echota, which exchanged all remaining lands of the Cherokee nation for $5 million and a homeland in Indian territory. The treaty had been negotiated without the knowledge, much less support, of Cherokee officials and against the wishes of the vast majority who remained. Leading the opposition to the Treaty Party, Chief John Ross gathered the signatures of almost 16,000 of the remaining 17,000 on a petition rejecting the treaty. Many Americans, especially New Englanders, also had rallied to the Indian cause and condemned the treaty as fraudulent. The strength of the resistance and the weakness of the government’s position were reflected in the vote of Congress, which passed the treaty by only one vote. Nevertheless Jackson remained obdurate; Indian removal must proceed.

While the Cherokee ostensibly had two years to prepare for emigration, Georgians now openly plundered their homes, took their money, and even demanded that they pay back rent on their farms. A few bands left almost immediately, but the majority insisted that they had made no treaty and refused to leave in spite of their rough treatment. Fearing acceptance would compromise their independence, they refused government provisions, preferring they said to live “upon the roots and sap of trees.” While their destitution and their determination continued to arouse sympathy, nothing could halt the course of removal.

In 1838, with only a small fraction having left voluntarily, General Winfield Scott was dispatched with 7,000 troops to forcibly remove the remainder. His proclamation declared:

“The President of the United States has sent me with a powerful army, to cause you, in obedience to the treaty of 1835, to join that part of your people who have already established in prosperity on the other side of the Mississippi. Unhappily, the two years which were allowed for the purpose, you have suffered to pass away without following, and without making any preparation to follow; and now, . . . the emigration must be commenced in haste, but I hope without disorder. . . . The full moon of May is already on the wane; and before another shall have passed away every Cherokee man, woman and child in those states must be in motion to join their brethren in the far West. . . . Thousands and thousand [of troops] are approaching from every quarter, to render resistance and escape alike hopeless. . . . Will you then, by resistance, compel us to resort to arms? God forbid! Or will you, by flight, seek to hide yourselves in mountains and forests and thus oblige us to hunt you down? Remember that, in pursuit, it may be impossible to avoid conflicts. The blood of the white man or the blood of the red man may be spilt and, if split, however accidentally, it may be impossible for the discreet and humane among you, or among us, to prevent a general war and carnage.”

A few thousand found refuge in the mountains of North Carolina, where their descendents continue to live today, but most were forced into stockades in preparation for the long journey. There they were so poorly supplied that many died of exposure, hunger and disease even before the trip began.

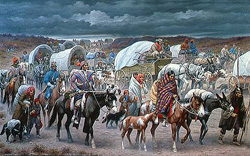

The Trail of Tears. Painted by Robert Lindneux in 1942. The Granger Collection, New York

Trail of Tears

During the summer one group was taken by river boat and train and the rest followed overland the next fall. The long trek is remembered as the “Trail of Tears” or “the Trail Where They Cried.” Corruption now added to their woes as tollgate operators and unscrupulous government agents cheated them and stole from them. Conditions along the trail were so dismal that an estimated 4,000 to 8,000 died, at least one-fourth of those who had set out on the journey. James Mooney, an ethnologist who interviewed the survivors years later noted, “The lapse of over half a century had not sufficed to wipe out the memory of the miseries of that halt beside the frozen river, with hundreds of sick and dying penned up in wagons or stretched upon the ground, with only a blanket overhead to keep out the January blast.”

Nor did arrival in Indian Territory end their travails. The protracted struggle over removal left them internally divided for years to come. The Ridges and Boudinot, the signers of the infamous Treaty of Echota, were assassinated and the Nation almost erupted into civil war. Once in their new homeland, they had to find ways to merge with those who had gone before and to reorganize their tribal life, as well as learn to make a living in a new environment.

William McIntosh

Although the Cherokee story is the best known chapter in the Indian removal tragedy, the other tribes of the Southeast fared no better. After the War of 1812, the Creek nation retained only a remnant of its ancestral lands. In 1825 a corrupt headman William McIntosh, acting without authority, sold all Creek lands in Georgia and most in Alabama, suddenly dispossessing towns occupied by several thousand people. McIntosh was subsequently executed by the Creek nation, but U.S. officials, knowing that he acted without authority, nevertheless proceeded to enforce the fraudulent treaty. Although President John Quincy Adams sympathized with their plight and made some efforts to protect them, the state of Georgia sent in survey crews and began appropriating the lands in defiance of the national government. When Jackson became president and recognized the state’s authority over Indians and their lands, he gave Creek delegates the same reception as the Cherokee. Even when Congress passed a plan providing for the allotment of plots to individual headmen, the states of Georgia and Alabama refused to respect Indian property rights.

What the whites did not take by force they gained through fraud. As one witness wrote, “I have never seen corruption carried on to such proportions in all of my life before. A number of the land purchasers think it rather an honor than a dishonor to defraud the Indian out of his land.” Homeless and with no means of support, the people were in desperate straits when a few warriors skirmished with local militia, providing the excuse for compulsory removal. Those who still refused to go willingly were placed in irons and forced out. Of the 15,000 forcibly removed approximately 3,500 died.

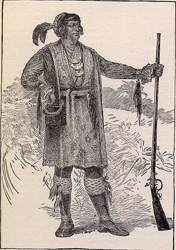

Chief Osceola

The Seminole resistance in Florida followed a different course. In the swamps and along the rivers of Florida this diverse group of refugees from other Southeastern tribes, which included a number of runaway black slaves, had banded together to resist white encroachment. Since Florida provided less attractive agricultural lands, they enjoyed greater autonomy for a limited time in the early part of the century. When pressured, they tended to fade into the swamps and launch guerilla attacks. In the 1830s as the government began trying to foist removal agreements upon them, the Seminole resisted under the leadership of Chief Osceola, who vowed to fight “till the last drop of the Seminole’s blood has moistened the dust of his hunting ground.” What followed was a prolonged, expensive, and bloody conflict. In an effort to remove about 1,500 people from the Florida swamps the government spent about $40 million and lost 1,500 soldiers. Though Oceola was ultimately captured through trickery and the Seminole were defeated, several hundred remained in the swamps.

No tactic adopted by the Indian tribes worked to halt the movement of whites into their lands. Resistance through legal challenge and persuasion proved no more effective than violence. Accommodations with white civilization were no more likely to staff off the settlers than nativist resistance. The result was a human tragedy of monumental proportions, exacerbated by the government’s failure to make adequate provisions or to protect lives and property. The policies adopted in the first half of the nineteenth century set the precedents followed henceforth. The same patterns were repeated with regularity as Native people were forced on to smaller and smaller reservations throughout the nineteenth century. The policies adopted in the latter part of the century and followed through much of the twentieth century continued trying to force the relinquishment of Native languages and traditions. Into the present day, Native people continue their struggle to find ways to be Indian in the midst of white prejudices and pressures.