Nullification

Tariffs rose once again to the political foreground in 1828, when Congress unexpectedly passed the Tariff of 1828. The tariff raised the fees on imported manufactured goods such as wool. The law, known as the Tariff of Abominations by its critics, increased duties even more. Southerners disliked the tariff, and saw it as a deterrent to English buyers who wanted to purchase American goods like cotton. The state of South Carolina was particularly displeased with the tariff. Although the rates were eventually lowered in 1832, opposition to the tariff had rooted itself deeply and grown into a crisis.

Did you know...

Calhoun used the rhetoric of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, written by Jefferson and Madison in 1798 to condemn and deny the constitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts, to support his ideas. The South Carolina Exposition and Protest would later be used when arguing a states’ right to secede from the Union over the issue of slavery.

South Carolina Exposition and Protest

The new tariff forced John C. Calhoun to take a stand, and he joined his state in denouncing the increased duties. Calhoun was a firm believer in the rights of the individual states, and saw these rights as a mechanism for southern states to protect their interests (cotton, slavery) from the actions of the more populous north. He wrote and published anonymously, the South Carolina Exposition and Protest (1828), arguing against the tariff. The Exposition declared that a state could nullify an act of Congress that it found unconstitutional. In this case, South Carolina claimed it could nullify the Tariff of 1828. Calhoun argued that the tariff was unconstitutional because it violated the trust of the states. If Congress passed a law that was unconstitutional, states had the right to nullify the law. Calhoun based his argument on the “compact theory” of government, claiming that the states gave the central government power when they became a part of the Union. If they could give power then they could also take that power away.

The Nullification Process at Work

Calhoun outlined the nullification process to work like this:

- Congress passed a bill (in this case the Tariff of 1828)

- A state could hold a convention to determine if the bill was constitutional. If found unconstitutional, the state could then nullify the bill.

- Congress had two choices:

- Congress could amend the Constitution to make the bill legal (a long and difficult process).

- Congress could change the tariff law.

- The state then had two choices:

- Accept the new law, or

- Secede from the Union.

Tariff of 1832

States Rights and Nullification Ticket. A broadside for South Carolina’s State Convention, 1832

Despite the protests, the Tariff of 1828 generated revenues for the government that helped pay a great many debts. With federal finances in better shape, Jackson signed the Tariff of 1832, which lowered the tariff rates generally but kept the protective aspects of the law of 1828 intact. Led by John Calhoun, South Carolina protested the protectionary aspects of the bill by holding a convention to nullify it, eventually threatening to secede.

Did you know...

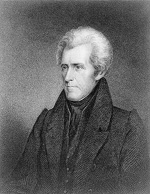

Andrew Jackson, drawn and engraved by J. B. Longacre between 1815 and 1845

Andrew Jackson owed his election to the southern slaver-holder vote but was a die-hard Unionist. Jackson declared nullification illegal and was the first president to declare the Union indissoluble. He said publicly that "Disunion, by armed force, is TREASON,” but privately said that he wanted to "hang every leader...of that infatuated people, sir, by martial law, irrespective of his name, or political or social position." Read Jackson’s Proclamation Regarding Nullification.

Nullification Proclamation

South Carolina’s actions outraged President Jackson, prompting him to issue the Nullification Proclamation in December of 1832, which denied a state’s right to declare any federal law unconstitutional. He called the action treason and threatened to hang the nullifiers himself. The Senate passed the Force Bill in 1833, giving Jackson the use of the army to force South Carolina to accept the bill and stay in the Union, which resulted in the stationing of both a naval and military force in South Carolina. No other southern state supported South Carolina or wanted to secede, so the state stood alone against the president.

Tariff of 1833

The great compromiser Henry Clay stepped in once again and managed to pass the Tariff of 1833, which further reduced rates over ten years. South Carolina, without aid from any other state, decided to accept the new tariff but nullified the Force Bill in a measure of protest—an action which was completely ignored by Jackson.

Did you know...

The crisis demonstrated Jackson’s executive power and the growing power of the presidential office. The Force Bill remained in effect, despite South Carolina’s nullification of the bill, and was used again in 1861 when South Carolina attempted once again to secede.