Andrew Jackson's Presidency

Andrew Jackson was born in a log cabin in the western territories. His father died two weeks before he was born and both his mother and two of his brothers died during the Revolutionary War. The British captured him when he was thirteen. When released, he promptly joined the militia, despite his young age. He emerged as a hero during the War of 1812, beating the British at the Battle of New Orleans and shortly afterward, taking Florida from Spain. In private life, he worked as a lawyer before becoming the first congressman from the newly created state of Tennessee.

Jacksonian Democracy

Jackson’s two terms as president took place against a backdrop of social and economic change in America. The population had been rapidly growing as immigrants flooded the country, and was accompanied by economic development. Amid these changes, there existed the movement toward a more widespread participation in government. This movement became known as Jacksonian Democracy, and Jackson himself symbolized the move toward greater democracy. The entire political system became available and open to more people. Though named for Jackson, many of the measures occurred before he took office. The increase in democracy included:

- The end of most political and property voting restrictions

- Presidential candidates were nominated, not appointed by a caucus

- The electoral college became an elected position instead of a nominated one

These changes increased the numbers of people participating in the political process. Between 1824 and 1840, the number of presidential voters rose from 350,000 to over 2.4 million, an increase of over 700 percent.

Politics of Personality

Jackson believed he was a true representative of the peoples’ popular will. He saw himself as the champion of the cause of the common man. He took this as a mandate to do whatever he believed right, greatly expanding the executive prerogative. As such a leader, Jackson felt it was his duty to crush legislation he deemed unfair and undemocratic. For example, other presidents vetoed bills only when they believed them to be unconstitutional. Jackson vetoed bills he did not like. He vetoed more bills than all other presidents combined.

Spoils System

Jackson believed that a democracy should be ruled by the people. He planned to rotate governmental offices, working on the principle that anyone who held an office for too long became corrupt. Jackson replaced 9 percent of the appointed officials in the federal government. While not an enormous amount, it did represent a new principle that evolved in practice into a spoils system—the firing of political enemies and the hiring of friends. Jackson’s enemies criticized the spoils system, claiming that Jackson’s newly hired friends were not fit or experienced enough for their jobs.

Political Infighting - The Imperial President

The spoils system led to political infighting as two men vied to be Jackson’s successors:

- John C. Calhoun

- Martin Van Buren

King Andrew the First. A political cartoon showing how some Jackson critics felt about the president

Both Calhoun and Van Buren hoped to become president after Jackson’s terms in office—winning his favor could ensure his endorsement.

The Eaton Affair

One particularly dramatic arena of the political infighting involved the wife of the U.S. Secretary of War, John Eaton. Eaton had married a recently widowed woman, Peggy Eaton. Her husband had allegedly killed himself after discovering her affair with Eaton. The wives of all the cabinet members snubbed her socially, including Calhoun’s. Jackson felt sorry for Eaton and befriended her. Calhoun’s rival Van Buren was a widower, and he also made friends with Eaton. Although of little actual importance, the scandal over Eaton helped Van Buren move closer to Jackson.

Martin Van Buren and Peggy Eaton side-by-side

Jefferson Day Banquet of 1830

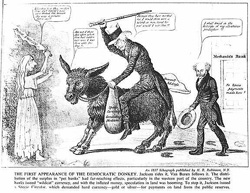

The first appearance of the Democratic Donkey. Jackson rides it and Van Buren trails behind. Jackson is slaying the “pet banks”

Van Buren scored again with Jackson following a special banquet held in honor of Thomas Jefferson. Calhoun asked Jackson to deliver a speech at the banquet in support of states’ rights. Instead, Jackson made a short toast to the United States, saying “our federal union “it must be preserved.” Calhoun was humiliated and engaged in a long winded talk about the rights of the states.

John C. Calhoun

Calhoun’s stand on Jackson’s Invasion of Florida, 1818

After the Jefferson banquet, Jackson received the last of the letters concerning Calhoun’s stand on his invasion of Florida in 1818, when Jackson had secured the area for the United States from Spain. As Secretary of War, Calhoun had proposed to punish Jackson for taking the territory without express permission. The letters unleashed a heated correspondence between the two men, nailing the lid on Calhoun’s presidential ambitions. Jackson turned his full support toward Van Buren.