Rise of Mass Democracy

The Revolutionary leaders believed that few citizens were objective enough to be able to vote or make public decisions wisely, so most state constitutions had reserved political rights to just the men who held a specific amount of property.

While the first generation of leaders enjoyed the benefits of wealth and education, by the 1820s ambitious citizens began questioning the notion that property, wealth, and education qualified a man to govern in a Republic. The western states were especially vocal in demanding an expansion of suffrage, or the right to vote.

In 1792 Kentucky entered the Union with the provision that every adult male would vote. In 1796 Tennessee became a state, providing suffrage to every male over twenty-one who paid a small tax. Other western states followed suit, including Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), and Alabama (1819).

The trend continued in the eastern states, too. Maryland and New Jersey expanded the property qualification for voting in the early 1800s, largely to try and keep farmers from moving west. Connecticut granted suffrage to all men who paid taxes or served in the state militia by 1817. Most of the states soon followed the western states’ lead and by 1840, almost 90 percent of white men could vote in local, state, and national elections.

The expanded suffrage had an enormous impact on politics in the United States, expanding democracy and allowing for greater influence and impact by ordinary white men.

But ordinary citizens did not usually get elected. Businessmen took office and steered funds toward their pet projects and entrepreneurs lobbied for legislative support through kick-backs. In order to facilitate this process, these men organized and mobilized average voters into cohesive political groups—factions or parties. Membership in political organizations rose dramatically during the 1820s.

Of course the expansion of suffrage was limited to white men. State legislators either ignored discussing the possibility of free African American male voting rights or expressly forbade it and no men talked of allowing women the right to vote.

Did you know...

Whig Parade

By the 1830s the National Republicans began calling themselves “whigs” and the two contending parties became known as the Democrats and the Whigs. This emergence of two distinct parties is known by historians as the Second Party System, making reference to the original Federalist and Republican parties.

Second Party System

Prior to the 1820s almost everyone active in politics was called a Democratic Republican, a name that was meant to distance politicians from the outdated “Federalist” label. By 1824, those individuals who supported Henry Clay’s American System began calling themselves National Republicans to differentiate themselves from the Democratic Republicans. John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay represented the National Republicans.

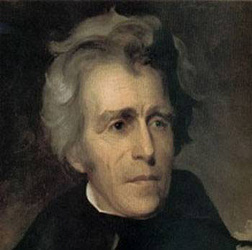

Andrew Jackson, who had been seething over the last election’s events for four years, began building support against his political enemies, the National Republicans by creating a new party called the Democratic Republicans or the Democrats. This new party wasted no time joining in what became a nasty campaign.

The election of 1828 revolved around personalities and sectional allegiances. The Democratic Republicans and their rivals organized efficiently, holding barbecues, and sponsoring entertainments to engender party loyalty. There were two main candidates:

Andrew Jackson

- John Quincy Adams—a National Republican. His enemies accused him of being a closet monarchist.

- Andrew Jackson—A Democratic Republican. His enemies reiterated his violent background.

Did you know...

Supporters of Andrew Jackson used the Battle of New Orleans anthem as their campaign song. The song is called Hunters of Kentucky (audio).

After ugly campaign smears that targeted the candidates personally and involved plenty of name-calling by both sides, Jackson won the election. He had easily mastered the ballots by appealing to the common people.