Cotton and the Economy

Eli Whitney. Illustration by Samuel F. B. Morse, 1822

By 1800 an important agricultural transition was taking place in the South. Cotton, grown for centuries on other continents, began gathering a foothold after the Revolution. Long staple cotton grew well in the tidewater area where the climate was moist and warm but would not grow in the more arid, upland areas. Short staple cotton was hardy and grew prolifically in the upland but contained rough seeds that took hours to separate from the fibers. For example, it typically took all day to separate the seeds from one pound of cotton.

Web Field Trip

Learn more about Eli Whitney at the Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop

Planters wanted to find some means of removing the seeds quickly and easily and this dilemma was solved in 1792 when Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin (short for cotton engine) that mechanically separated the cotton fibers and seeds. His hand-cranked box held a rotating cylinder with a fixed “teeth” that combed the seeds from the cotton,

Impact of the Cotton Gin

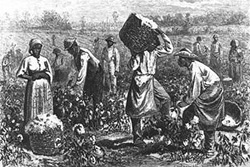

Slaves and cotton

Whitney’s invention enabled planters to clean up to fifty pounds of cotton fiber each day, fiber that found a ready home in England’s textile mills. The Industrial Revolution in England had led to the mechanization of spinning and weaving and textile mills that demanded endless supplies of raw cotton. New England merchants and shippers greedily purchased cotton from southern planters to transport to Britain to meet this demand.

Farmers, continually expanding westward, began growing short staple cotton in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, eastern Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas on large-scale plantations, worked primarily by slaves.

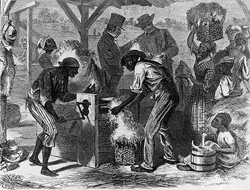

Illustration from 1869 projecting what the use of the first cotton gin might have looked like

Illustration from 1869 projecting what the use of the first cotton gin might have looked like As cotton production spread westward, so too did the institution of slavery. Planters in the Upper South began selling slaves to cotton growers in the Lower South, creating a huge domestic slave trade where enslaved Africans were spread throughout the frontier to support the expansion of cotton growing.

Cotton required massive amounts of human labor and this meant a life of endless toil for the slaves that worked in the fields. For example, John Brown, who eventually ran away from his master, later recalled being roused by a bell in February at four o’clock in the morning to pick cotton. He said that "I picked so well at first, more was exacted of me, and if I flagged a minute, the whip was liberally applied to keep me up to the mark. My being driven in this way, I at last got to pick a hundred and sixty pounds a day...." During the peak cultivation season, all hands worked as long and hard as they could.

The long hours invested by slave-labor soon made the southern states major players in the world economy. By 1830 cotton represented 41 percent of all exports from the U.S. and the capital earned from exports was invested in New England’s first manufacturing enterprises, expanding northern shipbuilding and commerce generally.