The Great Awakening

With all these new scientific and philosophical ideas floating around, many colonials turned away from a strict religious piety. Indeed, some critics felt that the Church of England itself had too easily accepted the detached God of Deism and become remote from the needs of ordinary people. By the 1730s the feeling of falling away from God provoked a revival known as the Great Awakening. Evangelism swept through the colonies, combating sin but also fighting the religious doubt caused by the Enlightenment. In an attempt to reassert the extreme piety of Puritanism against the rationalism of Deism, the Awakening ended up appealing to the emotions of the people. Instead of replacing the new philosophical ideas, the evangelism of the Awakening merged with the modern spirit. The Awakening advanced a critique of colonial society, established institutions, such as the Anglican Church, and colonial elites.

Jonathan Edwards

The religious movement began in different cities in the colonies, but all the revivals shared an emotionalism in common. The preachers’ sermons sought to replace the cold and unfeeling doctrines of Puritanism with a religion more accessible to the average person. Jonathan Edwards is one of the most famous evangelistic preachers. Edwards was one of America’s most important philosophers and theologians, and he sparked a spiritual revival in his church in Massachusetts that soon spread. He believed that his parishioners, especially the young, lived too freely, spending their time drinking and carousing. He thought the older churchgoers had become preoccupied with making and spending money. He wanted to touch his congregation’s hearts and to “fright persons away from hell.” His sermons vividly described the torments of hell and the pleasures of heaven. By 1735, Edwards reported that “the town seemed to be full of the presence of God; it never was so full of love, nor of joy.”

Listen to excerpts from Jonathan Edwards’s and George Whitefield’s sermons.

See the transcripts of the full sermons.

Jonathan Edwards |

George Whitefield |

The Folly and Danger of Parting with Christ for the Pleasures and Profits of Life (transcript) |

Did you know?

Benjamin Franklin heard George Whitefield speak and wrote of it later in his biography. “In 1739 arrived among us from Ireland the Reverend Mr. Whitefield, who had made himself remarkable there as an itinerant preacher. He was at first permitted to preach in some of our churches; but the clergy, taking a dislike to him, soon refus'd him their pulpits, and he was oblig'd to preach in the fields. The multitudes of all sects and denominations that attended his sermons were enormous, and it was matter of speculation to me, who was one of the number, to observe the extraordinary influence of his oratory on his hearers, and bow much they admir'd and respected him, notwithstanding his common abuse of them, by assuring them that they were naturally half beasts and half devils. It was wonderful to see the change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seem'd as if all the world were growing religious, so that one could not walk thro' the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.

He had a loud and clear voice, and articulated his words and sentences so perfectly, that he might be heard and understood at a great distance, especially as his auditories, however numerous, observ'd the most exact silence. He preach'd one evening from the top of the Court-house steps, which are in the middle of Market-street, and on the west side of Second-street, which crosses it at right angles. Both streets were fill'd with his hearers to a considerable distance. Being among the hindmost in Market-street, I had the curiosity to learn how far he could be heard, by retiring backwards down the street towards the river; and I found his voice distinct till I came near Front-street, when some noise in that street obscur'd it. Imagining then a semi-circle, of which my distance should be the radius, and that it were fill'd with auditors, to each of whom I allow'd two square feet, I computed that he might well be heard by more than thirty thousand. This reconcil'd me to the newspaper accounts of his having preach'd to twenty-five thousand people in the fields, and to the antient histories of generals haranguing whole armies, of which I had sometimes doubted.

By hearing him often, I came to distinguish easily between sermons newly compos'd, and those which he had often preach'd in the course of his travels. His delivery of the latter was so improv'd by frequent repetitions that every accent, every emphasis, every modulation of voice, was so perfectly well turn'd and well plac'd, that, without being interested in the subject, one could not help being pleas'd with the discourse; a pleasure of much the same kind with that receiv'd from an excellent piece of musick. This is an advantage itinerant preachers have over those who are stationary, as the latter can not well improve their delivery of a sermon by so many rehearsals.”

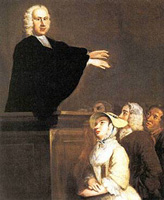

George Whitefield

More important to the revivalist movement, twenty-seven-year-old George Whitefield immigrated to the colonies from England, having preached through a series of Wesleyan revivals. While studying at Oxford, Whitefield had befriended John and Charles Wesley and had embarked with them on a highly structured system of study and personal piety with the intention of promoting spiritual growth. This “Holy Club” represented a response to the staid and conservative nature of the Anglican Church and its clergy. In his ministry, Whitefield said congregations were lifeless because “dead men preach to them.” He planned to ignite the fires of religious fervor in the New World. He arrived in Philadelphia in 1739 and soon preached to crowds of more than 6,000. Before long, he held revivals from Georgia through New England. Young and charismatic, Whitefield was an actor who performed for his audiences, physically demonstrating the miseries of hell and the joys of salvation. Audiences flocked to hear him speak, and he urged them to experience a “new birth,” or a sudden, emotional moment of conversion and forgiveness of sin. His audiences swooned with anticipation of God’s grace, some people writhing, some laughing out loud, and some crying out for help.

The Awakening proved popular, especially along the frontier and in the southern colonies. Common folk responded with great enthusiasm. The Baptists and the Methodists, two popular Protestant denominations, grew enormously as a result of the revivals. Methodism originated in the work of Anglican priest John Wesley. Wesley, along with his brother Charles, and George Whitefield, advocated prayer, Bible study, and personal piety applied in a structured manner as a means of personal transformation and growth. Critics of the three at Oxford derided them as “Methodists” for their methodical approach to Christian practice. From these beginnings in the 1720s, Methodism emerged as a current of practice and belief within the Church of England; however, Methodist preachers and congregants were subject to persecution by the established church. Wesley advocated evangelistic outreach to those alienated from or ignored by the Anglican Church. Both Whitefield and Wesley traveled to and helped spread Methodism in America, but eventually parted ways theologically, with Wesley and the bulk of Methodists embracing an Arminian (salvation for all) rather than a Calvinist (predestination) approach to salvation.

The Baptists had old roots in the colonies, but their message of individual salvation, the equality of all before God and exhortations to personal piety spread southward along with Methodism in the mid-1700s. Baptists exhibited both Calvinistic and Arminian tendencies in a widely divergent and growing church polity. While Methodist growth was in part inhibited by the requirement that ministers be trained at a university, Baptists argued that any man could be “called” to preach and that formal education was not necessary. The contentious and diverse sect emphasized the right of individuals to interpret the Bible for themselves, strict congregationalism, and an obligation on the part of Christians to proselytize. Moreover, the Baptist’s insistence upon man’s equality before God and stress upon personal piety contributed to increasing tensions between them and the society in which they lived. Worship was highly emotional and often lacked structure. Critics often described Baptists as “enthusiasts,” a term of derision in the days when polite society frowned upon outpourings of emotion and intellectual conventions tended toward detached rationality.

George Whitefield preaching, contemporary woodcut

Did you know?

In addition to playing a crucial role in changing the nature of religion in the colonies, the Great Awakening had political consequences, too. As the revival spread through the colonies, it transcended some of the differences that had emerged between the different regions. The Awakening has been called the first truly American event because it formed a bond or commonality between the different colonies. Some historians believe that without the Awakening, which occurred because of the spread of Enlightenment ideals, there would have been no Revolution. They argue that the evangelicals touched more the just the colonials’ souls. Historian Rhys Isaac has even described the Baptist variant of the Great Awakening as a “countercultural” development. By emphasizing the personal dimensions of salvation and undermining the established religious institutions, the Awakening encouraged a spiritual diversity that paved the way for the eventual separation of church and state. The movement also nourished the egalitarian temper of the colonials and developed the first sense of an American distinctiveness that hastened the break from England.

The average colonial found the message appealing. Though they might not be well educated, the new religion seemed to say that they could come to know God’s grace as well as anyone else. Although the revivalists like Edwards had hoped to return people to a more pious lifestyle, the Awakening backfired in that attempt. Edwards’s careful adherence to Calvinist theology did not resonate with as wide an audience as did the broader message of the Methodists and Baptists. Instead the crowds heard a different message: they formed their own meaning from the sermons, concluding that salvation was available to all, not merely to a few chosen elect. The people believed that the individual was the most important person in the salvation experience. This new evangelical Protestantism spread rapidly, with the unlettered articulating their own understanding of the Gospel and Scripture without the strictures of a church hierarchy. The primacy of personal religious experience promoted varied interpretations and the evolution of new sects. The Great Awakening in many ways democratized religion in the colonies, turning it away from the old patterns of subservience to church and ministers and laying God at the feet of each and every individual. Additionally, the Great Awakening renewed an interest in intellectualism, which resulted in the founding of new universities and the expansion of published texts.

Southern colonial elites found the Awakening threatening for a variety of reasons. First, the movement undermined the authority of the Church of England, an institution considered vital by many to English identity and social order. On another level, the Awakening threatened the social hierarchy. Evangelicals criticized cherished elite pastimes—gambling, dancing, drinking—as well as fashionable dress and norms of personal deportment. Their message not only criticized elite piety, but even suggested that their temporal authority in determining social norms and even governance was somehow suspect. This eroded the societal deference that helped define social class in day-to-day life. Awakening ministers actively evangelized among the slaves. While hardly a movement for racial equality, the religious doctrines propagated by groups such as the Baptists threatened to disrupt order on colonial plantations. Planters at this point had made only limited efforts to inculcate Christianity among their slaves. The Awakening brought those same slaves into contact with the most radically egalitarian elements of colonial Protestantism. Finally, the highly demonstrative nature of evangelical worship and the direct manner in which its adherents spoke of their religious experiences ran counter to the stoic and reserved expectations of social discourse among 18th Century elites.

Ultimately, the Great Awakening had a push-pull effect upon the coming of the American Revolution. In Virginia, for example, upper-class support for the Revolution has been interpreted by some historians as springing from elite frustration at the inability of the Anglican Church to effectively anchor the deferential society, leading to a sense that colonial elites would have to step in to fill the vacuum. Conversely, the pull of the growing evangelical tide eventually forced elite patriot leaders to move in the direction of supporting greater religious liberty to attract middling and lower-class whites to the cause of independence.