Colonial Cities

During the seventeenth century, the thirteen British colonies developed separately and distinctly. The large cities of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston had more contact with London than they did with each other. At the close of the colonial period, Philadelphia was the largest, boasting a population of around 30,000—second only to London in the British Empire. New York was the second largest city in North America with around 25,000 people. Boston’s population was 16,000, while Charleston’s numbered 12,000.

Despite the fact that fewer than 10 percent of all colonials lived in cities, cities set the tone for commerce, politics, and culture, serving as religious, economic and cultural centers. Society was rigidly stratified during the period: merchants at the top of the order, craftsmen, retailers, and innkeepers followed, with sailors, unskilled workers, and small artisans at the bottom. Over time, class stratification became more pronounced and wealth became concentrated among a few. But all colonials became consumers, wanting luxury items that made life more pleasant and that reminded them of England. Imports increased, and colonials purchased:

Did you know...

Want to see how colonials dressed and how clothing marked a person’s social status? Dress the colonial.

|

To have these goods, colonials had to learn to be producers as well. The above items could best be obtained by producing exports for trade, exports such as foodstuffs or raw materials. A market for these goods could be found in the English West Indies, where almost all efforts and resources were devoted strictly to sugar production. In order to function, these areas depended on foods and goods from elsewhere. American colonial port cities were centers where these crucial products could be processed and sold or traded for other needed and desired commodities from England or the West Indies.

The Cities

Boston Harbor

Boston was the economic center of New England. Bostonians worked in shipyards, engaged in fishing, as well as logging, iron works, and wool processing. Of these shipbuilding was the most important of Boston’s industries. By the eighteenth century, Boston maintained fifteen shipyards. Most of Boston’s skilled workers were involved directly or indirectly in the shipbuilding trade, which bolstered other industries like timber, sawmills, sail manufacturing, and rope making.

New York, known for its diverse population, was important as a source of foodstuffs for England’s colonies in the West Indies. Wheat and corn were produced and sold in exchange for goods from England or the West Indies. Lumber and wood products from the thick surrounding forests were also important exports.

Philadelphia also had a bustling shipbuilding industry, supplemented by the production of wood products from the area’s extensive forests, sail manufacturing, and rope for sea-bound ships. This port city also processed the important staples of flour and meat for export to other colonies.

The Southern port city of Charles Town (now Charleston) focused its economy on nearby agricultural products. Warm temperatures and a long growing season meant that South Carolina could produce large quantities of foodstuffs for export. Rice and indigo were grown on plantations and sold to Europe or the West Indies. England’s busy sugar colonies also relied on Charleston for shipments of meat and firewood. The sale of deerskins proved another lucrative aspect of the city’s economy.

Travel between the Colonies

Traveling between the colonies was difficult. The first roads were Indian trails, eventually widened by use. These rough roads made for slow passage across the countryside and every few miles, a place was needed for weary travelers to stop and refresh themselves and their animals. Taverns provided safe havens, overnight rest stops and refueling stations. Colonials gathered in taverns to relax, drink, and gossip about politics and business.

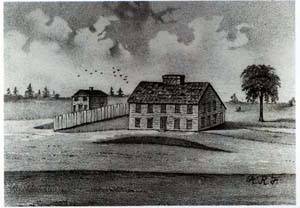

Ames Tavern, Massachusetts