The Middle Passage & Slave Agency

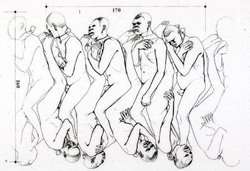

Position in which slaves were kept on ship; Jean Boudriot, Traite et Navire Negrier l'Aurore, 1784

Africans forcibly removed from their homeland were stuffed into cargo vessels and made to endure the brutal “middle passage” from West Africa to the West Indies where they made worlds of their own. They were branded with cattle iron and assigned a sliver of space below deck. Many resisted and were killed in Africa. Others committed suicide after boarding the ships by throwing themselves over to the sharks. Over 15 percent died from dysentery on the way to the Americas. Although most mutinies failed, a few succeeded. Detailed accounts of fifty-five slave mutinies exist between 1699 and 1845 and there are references to hundreds more. The mutinies prove that slaves did not submit peacefully to being carried away like chained animals, but rather fought back when they could.

The period of time sailing from Africa to the Americas is known as the Middle Passage. This passage is part of a larger shipping pattern know as the Triangular Trade. An example of the Triangular Trade would have a British sea captain beginning his trip in England and sailing from there to Africa (the first leg of the triangle). The captain anchored off the coast of Africa while filling his hold with slaves, a process that could take up to nine months. In exchange for the slaves, he would trade his cargo, often manufactured goods, woolen cloths, guns, or rum. It could take months to fill a ship’s hold with slaves and during the interim disease ran rampant as Africans from differing tribes mixed. Fully loaded with the enslaved, the captain sailed to the Americas (the second leg of the triangle). The captain would try to make the quickest voyage possible to the Americas but even so, it might take two months. Once in the Americas, the Captain sold the slaves, filled his hold with more cargo, usually rum or natural resources like tar or furs, and returned to England (the third and final leg of the triangle). Explore the following interactive, which includes clips from the movie La Amistad, to learn more about the Middle Passage.

The Middle Passage, when the ship was loaded with slaves, was the most dangerous part of the triangle trade route but also the most profitable.

Did you know...

English slave traders followed one of two schools of thought when they loaded slaves aboard ship.

- Loose packers believed that if a slave was given more room, fed better, and allowed a degree of freedom aboard ship, fewer would die and those who lived would be healthier and sell for a higher price immediately upon docking.

- Tight packers believed that it was more profitable to fit as many Africans aboard ship as possible. Though they had little room to move and little food, those who lived could be fattened up before being sold. Starting with more captives compensated the higher death rate.

Which philosophy proved more popular? Most traders were tight packers. The tight packers believed that the greater number of slaves available to sell per ship outweighed the risks of higher death rates among the slaves.

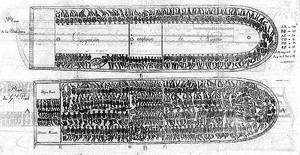

Enslaved Africans packed tightly into a ship. Résumé du témoignage donné devant un comité de la chambre des communes de la Grande Bretagne et de l'Irelande, touchant la traite des negres (Geneva,1814)

Slaves found life aboard ship grueling. If the weather was good, the traders brought the Africans on deck around eight in the morning, attaching the men by leg irons to a great chain that ran along the bulwarks on both sides of the ship. Women and children were allowed to wander the ship freely. Served a meal around nine, the sailors fed the captives boiled rice, millet, corn meal, stewed yams, and plantains. Each person was given a half-pint of water.

After the meal the slaves were forced to exercise. Called the “dancing of the slaves,” traders believed that the hopping, singing, and beating of drums and sticks would ward off sadness. Today we would call this depression and depression was a constant problem for traders. Some slaves preferred to commit suicide rather than accept their fate, a fate few of them understood clearly. Rumors circulated in Africa that white men were cannibals, and some of the enslaved believed that they were being kidnapped to be eaten later.

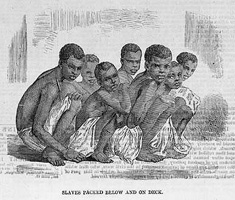

Most of the slaves were taken first to the Caribbean. Upon arrival in the West Indies many became ill. Slaves lacked immunities to diseases such smallpox, as well as several intestinal disorders. As a result, they died in large numbers. Captains sold most slaves at public auctions or at private wharves. Those not healthy enough to command a price were left to die. If they were sold in the West Indies, hard work soon wore them down. In the West Indies, masters worked slaves with no regard for their lives, health, or comfort. They were seen as an investment to generate profit, like cattle. As they became cheaper, which they did throughout most of the century, the treatment worsened. The price of sugar continued to increase. Between 1700 and 1730, for example, Barbados imported over 80,000 slaves. Only 4,000 were born on the island. Owners essentially treated these enslaved Africans like a disposable resource.

Did you know...

English slave-trader John Newton (1725–1807) was returning home during a storm when he wrote the hymn, “Amazing Grace." He converted to Christianity, though he continued in the business of slave trading for many more years. After leaving the slave trade and becoming a minister, he continued to hold investments in slave trading companies and socialize with slave captains. He did not criticize slavery in his sermons until much later, long after he wrote the hymn.

Slaves in North America, where the conditions were not as brutal as in the West Indies, had a different experience with better opportunities for developing societies of their own. The most challenging aspect of forming a slave society was negotiating a wide range of cultures. A slave master might have seen his world in black and white, but slaves looked around and saw Angolan, Igboo, Jamaican, and Congo. That is, they recognized the cultural differences in language and religion among the wide variety of the enslaved. Some slaves had been “seasoned” in the West Indies before coming to North America, while others came directly from Africa. There was a swirl of cultural differences to be negotiated.

Slaves packed on deck. The Illustrated London News (June 20, 1857), vol. 30 p. 595

Slave Culture

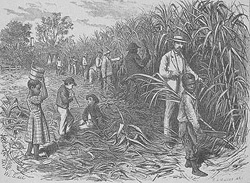

Slavery provided a common bond among captives, and these bonds led to a distinctly unique slave culture in the Chesapeake and the Carolinas. Growing tobacco created a different kind of slave society than the kind created on rice plantations. In the Chesapeake region, tobacco required constant attention, and slaves worked specific tasks under the close watch of an overseer, working in gangs engaged in repetitive work, from sun up to sun down.

Tobacco plantations were self-sufficient systems that required many slaves but they also offered opportunities for slaves to develop prized skills. For example, slaves learned to make nails, riding gear, and do woodwork, regularly working as coopers, sawyers, carpenters, spinners, weavers, food processors, and tanners. They provided food, constructed buildings and made clothes and tools for themselves and their masters. They did more than just mindless, robotic tasks, and they had some chance to develop a sense of dignity through work.

The Great South

Rice plantations led to a different set of opportunities. Carolina planters behaved more like West Indian planters in their choice to import rather than obtain slaves by natural increase. Nevertheless, it was not so brutal as to prevent the formation of a Carolinian slave culture. Rice did not require the constant, year-round attention that tobacco did. It was brutal work but it was work done in spurts rather than in a sustained fashion. Slaves did not work in gangs, but in something called the “task system.” Basically, the overseer met with the slaves in the morning and assigned them a specific task for the day. When completed, slaves had the rest of the day to themselves. This often amounted to half a day to grow and sell vegetables, row boats for local whites for wages, raise chickens or catch fish to improve their diet, or make instruments and play music for their enjoyment. Again, it provided some opportunity to develop a sense of dignity and community within the confines of this brutal labor system.

Did you know...

American Indian (Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Arkansas, among others), African, French, and Spanish cultural groups came together, influencing each other bi-directionally in Louisiana, creating a culture where groups worked together to form a distinct Creole culture. “The Africans arrived in an extremely fluid society where a social hierarchy was ill defined and hard to enforce. . . . A slave in Africa probably had more rights than a poor white in France, and certainly more rights than a poor white in French Louisiana. . . . Some of them [Africans] demonstrated sophisticated knowledge of their rights under the Code Noir.” (Hall 128) The racial hierarchy enforced in other colonial regions of the world seemed less strict in French Louisiana. In fact, social position in society lacked racial definitions. Evidences of interracial marriages and the early creation of free populations of blacks in Louisiana, reveal a comparatively less restrictive race relationship in Louisiana.

Slaves retired from the field at the day’s end to small shacks set apart from the master’s house. There they built a community within a community, and shared food, played music, passed along medical advice, and built strong networks of friendship and kinship among themselves. Although masters were reluctant to legally recognize slave marriages so that they maintained the freedom to sell slaves without worrying about a spouse or children, slaves did marry through informal ceremonies. They also carried out baptisms and established spousal roles and expectations, forming extended families that included biological and adopted children.

Slave life; Harper's Weekly, May 21, 1870, p. 321

Religion

Religion was an important aspect of slave culture. Masters more often than not worked to impose Christianity on slaves, assuming that the idea of heaven waiting for the long-suffering Christian would lessen the chances of the slaves rebelling. But other masters opposed religious instruction on the grounds that a Christian message of equality before the eyes of God was an obvious contradiction. The slaves tended to incorporate Christianity selectively into their own religious practices, combining Christian and African traditions.

Dissent

Slaves eked out what freedom they could within the confines of slavery. They married, formed families, had children, practiced their religion, cooked their own food, and even ran small businesses. And sometimes, not very often, but sometimes, they expressed their agency by rebelling. Building separate cultural and economic spheres was one way to preserve dignity and a sense of humanity; another was to lash out at the system that enslaved them.

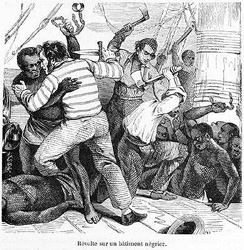

Mutiny; Albert Laporte, Récits de vieux marins (Paris, 1883), p. 267

Slaves poisoned their master’s food, killed family pets, broke tools, slowed work, and stole from their master. They snuck out at night to visit other plantations, sassed their overseer, and faked illness. But open rebellion was rare and difficult to carry out. The likelihood of getting caught was high and the consequence was certain death. In such a racially divided society, moreover, rebels were carefully watched and automatically marked.

But revolt did occur, as did mass rebellion. In September 1739 South Carolina newspapers reported that nearly seventy slaves had gathered in the dark, escaping to Spanish Florida, with more trickling south over the next few weeks. Planters began to worry about the drain of “rice slaves” out of the colony, especially when later in the month several hundred slaves initiated a mass exodus toward Florida in what is now called the “Stono Rebellion.” Along the way they killed whites, largely out of fear that they would spoil the escape. Approaching Florida they chanted “liberty, liberty, liberty.” But before they could secure their freedom, they were caught by a colonial militia, who killed two-thirds of the runaways. In the coming months, planters executed sixty other slaves suspected of helping to foment the rebellion and enacted the “Negro Act,” a law that drastically curtailed slave privileges like their ability to earn their own money or learn to read. The colonies were governed by whites, and this became brutally clear as colonial America emerged into a mature society.