Southern Colonies

The Old Plantation, c. 1790. Credit: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Museum, Colonial Williamsburg.

The economy of the southern colonies dictated many of the differences in lifestyles that resulted in the region. Good, cleared land and a mild climate meant that the people living in the southern colonies grew staple and exotic crops for the cash market. Tobacco became the first staple crop grown large-scale, and soon became the economic foundation of Virginia and North Carolina.

Settlers in these colonies planted as much tobacco as possible, sometimes planting right up to the streets of their towns. Colonists in South Carolina tried growing tobacco, but the crop was not suited to the land. Instead, South Carolinians found that rice grew well in the soggy bottoms and indigo flourished, which could be sold to the British woolen industry to dye products blue. The southern colonies also produced lumber, tar, pitch, turpentine, furs, and cattle in abundance. The southern colonies included:

Colonial woman

- Maryland

- Virginia

- North Carolina

- South Carolina

- Georgia

Cash market crops require large amounts of land and a large work force. It was easy to get land-there was so much land in the Americas that at first it seemed almost free for the taking-but labor was scarce.

Did you know...

Elizabeth Springs indentured herself in exchange for a passage to the Americas. She served in a Maryland household and wrote home to her father, complaining of the terrible treatment, begging her family to send her a blanket.

Maryland, Sept’r 22’d 1756

Honored Father

My being for ever banished from your sight, will I hope pardon the Boldness I now take of troubling you with these, my long silence has been purely owning to my undutifullness to you, and well knowing I had offended in the highest Degree, put a tie to my tongue and pen, for fear I should be extinct from your good Graces and add a further Trouble to you, but too well knowing your care and tenderness for me so long as I retain’d my Duty to you, induced me once again to endeavor if possible, to kindle up that flame again. O Dear Father, believe what I am going to relate the words of truth and sincerity, and Balance my former bad Conduct my sufferings here, and then I am sure you’ll pity your Destress Daughter, What we unfortunate English People suffer here is beyond the probability of you in England to Conceive, let it suffice that I one of the unhappy Number, am toiling almost Day and Night, and very often in the Horses drudgery, with only this comfort that you Bitch you do not halfe enough, and then tied up and whipp’d to that Degree that you’d not serve an Animal, scarce any thing but Indian Corn and Salt to eat and that even begrudged nay many Negroes are better used, almost naked no shoes nor stockings to wear, and the comfort after slaving during Masters pleasure, what rest we can get is to rap ourselves up in a Blanket and ly upon the Ground, this is the deplorable Condition your poor Betty endures, and now I beg if you have any Bowels of Compassion left show it by sending me some Relief, Clothing is the principal thing wanting, which if you should condiscend to, may easily send them to me by any of the ships bound to Baltimore Town Patapsco River Maryland, and give me leave to conclude in Duty to you and Uncles and Aunts, and Respect to all Friends

Honored Father

Your undutifull and Disobedient Child

Elizabeth Sprigs

Indentured Servants

Indentured servants performed much of the labor during the early years of colonization and were mainly of English, Irish, or German heritage. These servants got their name from the indenture or contract they signed, binding themselves to work for a number of years (usually four to seven) to pay for their transportation to the New World. Voluntary indentured servitude accounted for half of the white settlers living in the colonies outside New England.

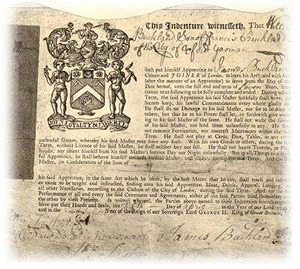

Indentured servant contract

After serving their years of indenture, the servant was free to go and acquire land on their own. Some of these former servants did well for themselves, many became political leaders or plantation owners, although most remained part of the poorer classes. Until the latter half of the 1600s, white indentured servants comprised the dominant source of labor in the Americas and it was not until the 1680s and 1690s that slave labor began to surpass the use of white indentured servants. Although African slaves cost more initially than indentured servants, they served for life and quickly became the labor force of choice on large plantations.

Life in the Southern Colonies

In the early 1600s most southern colonists were poor and men outnumbered women three to one. Mortality rates were higher in the south because of greater disease risks—we now know that mosquitoes, a far more constant threat in the south, carried many of these diseases. On average, men lived to be forty and women did not live past their late thirties. One quarter of all children born died in infancy and half died before they reached adulthood. Most Southern colonials lived in remote areas in relative isolation on farms or plantations with their families, extended relatives, friends, and slaves. They had little opportunity for social activity but when they did entertain, they might have visitors for weeks. Anglicanism formed the dominant church, although southerners were not particularly religious.

By the 1700s life settled down for the southern colonials and more rigid social classes formed. A gentry class emerged, building large plantation homes and imitating the lives of the English upper crust. Many of the plantation owners relied heavily on credit to maintain their leisured lifestyles.

Did you know...

The mixing of different nationalities and religions did not always result in complete toleration but often economics made it in everyone’s best interest to get along. A Frenchman named J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, traveling through the middle colonies, noted the arrangement and commented on it in a book he published called Letters From An American Farmer. De Crevecoeur described the blurring of national and religious differences that occurred in the middle colonies, and he said that this represented the forming of a “new race.” He was the first person to talk about a distinct “American” identity.